"Xiaomi Methodology" Research I: How Lei Jun Conquers Mobile Phones, Home Appliances, and Automobiles with One Strategy?

![]() 06/19 2025

06/19 2025

![]() 654

654

This article is based on publicly available information and is intended for information exchange purposes only. It does not constitute any investment advice.

Recently, Lei Jun attended Xiaomi's investor conference in 2025. This year marks the 15th anniversary of Xiaomi's establishment. Besides answering investors' questions about the business, Lei Jun discussed the moat he has built for Xiaomi.

Even in Lei Jun's own words, Xiaomi's moat is not different from public perception. He simply uses more clever rhetoric to replace flat expressions, attributing the design logic questioned by the public to a "high-end product methodology," the cost-effectiveness praised by Xiaomi fans to a "blockbuster model," and the unparalleled marketing capabilities mentioned by competitors to a "new retail model."

Of course, blockbusters, high-end products, and new retail marketing are not isolated but interconnected: The creation of blockbusters cannot be separated from the reform of the retail model, and the advancement of high-end products also relies on the capital and technological strength accumulated by "blockbusters."

All these independent industrial models collectively constitute the current "Xiaomi Methodology" that dominates home appliances, automobiles, and smart hardware (IoT).

As a model of advanced manufacturing in China today, understanding Xiaomi should not be limited to design controversies and personal IP marketing. Therefore, we have decided to delve into the underlying logic of how the "Xiaomi Methodology" mentioned by Lei Jun was formed and operates, from a longer-term perspective, in an attempt to learn from the thinking of outstanding entrepreneurs.

As the opening article of the "Xiaomi Methodology Series" research, we will focus on the "Blockbuster Model" today: Why do Xiaomi products, despite controversy, always become the "standard" for market comparison?

01

Product Threshold: Industrial Design as Innovation

In 2015, Yutaka Yuno, who once worked in research and development positions at Hitachi, Elpida, and other leading Japanese electronics companies, wrote about the predicament of the Japanese electronics manufacturing industry and published the book "Lost Manufacturing: The Defeat of Japanese Manufacturing." The book emphasizes the decline of Japan's white goods and television industries.

Yutaka Yuno uses a very simple metaphor: the argument between a "Sony husband" and a "Renesas wife." The Sony husband tries to convince his wife of the clarity of the TV's picture quality with BRAVIA technology, while the wife retorts, "I only care about more hard drive space to store movies. Clarity that the naked eye cannot distinguish means nothing to me."

Yutaka Yuno describes the dilemma of the Japanese TV industry as a "misunderstanding of innovation": When the thickness of a TV decreases from 30mm to 10mm, it represents a leap in product technology across cycles. However, a decrease from 10mm to 8mm cannot be called effective innovation; it's merely a form of self-comfort for technicians.

The more popular the term "innovation" becomes, the harder it is to achieve true innovation. The Japanese manufacturing industry is obsessed with defining innovation as technological innovation, while across the ocean in the United States, design and trend creation have achieved innovation in another sense, giving birth to Apple.

In 1980, riding the wave of reform and opening-up, a group of Japanese companies entered the coastal Chinese market. Hitachi (HITACHI) took the lead in establishing a home appliance China trading department, located in the middle section of Wuyi Road, Fuzhou, and officially constructed the first modern home appliance manufacturing plant, "Fujian Hitachi Television Co., Ltd."

In the same year, electrical joint ventures sprang up like mushrooms in the coastal reform and development zones. TTK Household Appliances Co., Ltd., located on Eling South Road, Huizhou, Guangdong, emerged, and the Guangming Overseas Chinese Electronics Industry Company was established across the river. The former is the predecessor of TCL, which is now the absolute leader in the TV field, and the latter is the predecessor of Konka Group, which was once powerful.

Similarly, Gree's predecessor, "Guanxiong Plastic Factory," was a raw material supplier for coastal joint venture TV factories, and Midea also started by relying on contract manufacturing for coastal home appliances, eventually transforming after acquiring Toshiba's Wanjiale Electric Factory.

In other words, traditional white goods manufacturers were born under the background of Sino-foreign joint ventures during the reform and opening-up and gradually grew stronger through the "technology-industry-trade" route. However, the development thinking followed by these enterprises is often rooted in the basic system constructed by the Japanese manufacturing industry in the last century. This has also created a problem: All older generation white goods manufacturers, limited by the cognitive framework of their managers, have almost fallen into a dilemma similar to that of the Japanese electronics manufacturing industry.

For traditional electronics manufacturing, regardless of whether individuals admit it or not, there has already been a technological stagnation in terms of pure technological innovation. The technological innovations that most manufacturers struggle with are no more than a few millimeters in thickness and brightness that is difficult to distinguish with the naked eye.

Xiaomi, on the other hand, was born in the era of Apple and does not have the historical burden of relying on Japanese corporate culture or an excessive obsession with technological innovation. Therefore, the starting point for Xiaomi's transformation of the manufacturing industry is essentially the industrial design logic of Apple products.

In the book "Xiaomi Ecological Chain Battlefield Notes" published by Xiaomi Ecological Chain's Gucang Academy, details of Xiaomi's early lead in IoT were disclosed. At that time, Lei Jun recognized the IoT trend and found Liu De, a member of the founder's team, to serve as the head of the ecological chain. Liu De himself graduated from the Art Center College of Design in the United States.

Therefore, the logic behind the birth of the earliest batch of Xiaomi IoT products, such as power banks, was that the IoT team saw that similar products on the market were of varying quality, lacking brand language in industrial design, and failing to meet the demands of new-era consumers who pursue emotional expression beyond practicality.

Of course, there are bound to be dissenting voices, as some enthusiasts do not recognize Xiaomi's design, believing that it is imitating Apple and MUJI. However, for Chinese electronics manufacturing products in the late 2010s, Xiaomi's "imitated" design was undoubtedly a dimensional attack.

Image: Comparison of contemporary product images, Source: ZOL, Xiaomi's official website, and online images

In terms of quality and technology, all of Xiaomi's early products were not different from contemporary products, and might even have disadvantages due to insufficient manufacturing experience.

However, by offering prices far lower than Apple's, Xiaomi satisfied users' pursuit of Apple's aesthetics. This design language of modern industrial aesthetics has also spread to the traditional white goods field. At least for consumers, it is very recognizable, allowing people to immediately identify Xiaomi's products.

Industrial design language laid the foundation for Xiaomi's early IoT development and established the lower limit of Xiaomi's products, becoming the sharpest sword for early Xiaomi to stir up traditional manufacturing -

It can be seen that design improvement is also a form of innovation during periods of technological stagnation?

02

Mainstay: The Originator of "Small Orders, Quick Response"

If Xiaomi's products relied solely on the lower limit set by industrial design, they would not have become the "standard" for mass consumer products. Building on industrial design, Xiaomi has found an iterative methodology for its products: pursuing efficiency, rapid iteration, and finding the greatest common divisor.

Gao Xiongyong, the former vice president of Xiaomi TV, once revealed a set of Xiaomi's blockbuster logic, which mentioned a crucial iterative logic: all good products need to undergo iteration to maintain continuous competitiveness.

In Xiaomi's view, traditional manufacturing enterprises were born in an era when per capita purchasing power and production levels were relatively low, and durability was the pursuit at that time. However, it is unimaginable for a product to be sold for 10-20 years in the Internet era. Therefore, the speed at which products are kept up-to-date is very important.

Compared to the research, production, and sales cycles of mature white goods enterprises, Xiaomi's IoT overall efficiency is faster. It first launches a product that meets the design language and then forms a relatively perfect product through iteration.

The disadvantage of this approach is that Xiaomi's first-generation products often do not have a good reputation. The logic of not buying Xiaomi's first-generation products is still prevalent online. However, relying on industrial design and relatively low prices, it does not excessively damage brand strength.

Image, Zhihu user comment, Source: Zhihu user Damixiexie

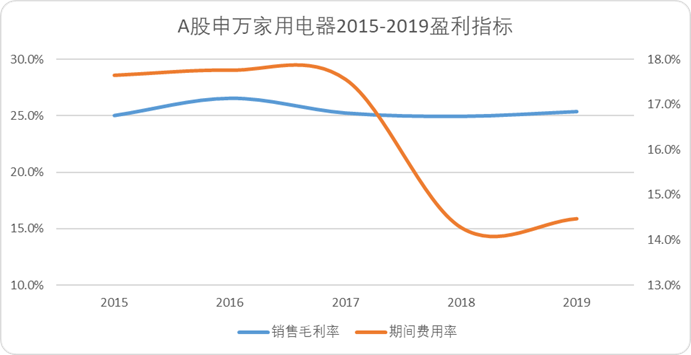

Therefore, we can see that the profit model of household appliances and white goods enterprises is closer to that of traditional manufacturing, which means having a relatively stable gross sales margin (with relatively fixed products on the market) and then spreading costs through scale to ultimately achieve marginal returns. This is particularly evident during weeks of relative technological stagnation, such as 2015, when Xiaomi's IoT exploded.

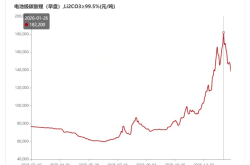

Image: Trend of profit indicators for home appliances in the A-share SW sector, Source: Choice Financial Client

However, listed companies related to the Mijia industrial chain often have low gross margins accompanied by relatively stable and continuous investment, and there is no significant decrease in period expenses as production and sales margins grow.

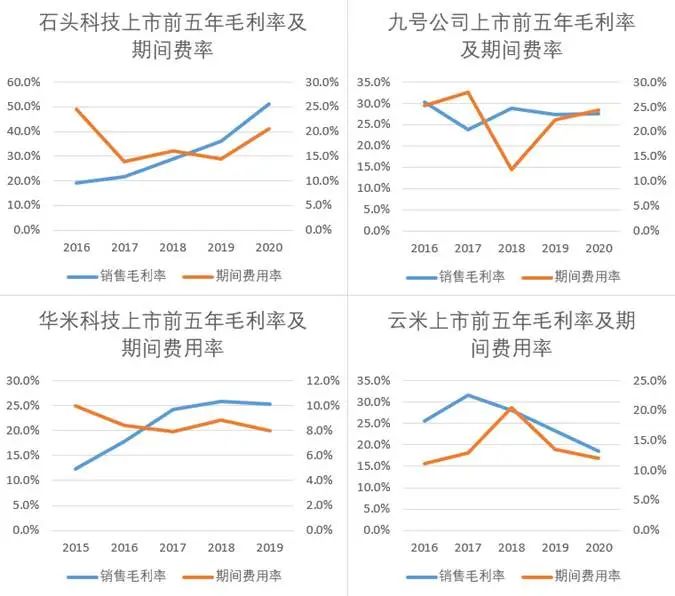

Taking the following chart as an example, the period expense ratios of four typical Xiaomi IoT ecological chain enterprises do not show a significant dilution effect during their initial public offerings, indirectly confirming Xiaomi's logic of rapid iteration and sustained investment to create blockbusters.

Image: Gross margin and period expense ratio of some Mijia chain enterprises, Source: Choice Financial Client

Xiaomi also has different views on "iteration." When facing technological stagnation, most electronics enterprises usually pursue so-called "large and comprehensive" functionality in their iterative products, hoping to defeat competitors through broader demand coverage.

However, Xiaomi's iteration logic is permeated with abandonment. In the two books "Xiaomi Ecological Chain Battlefield Notes" and "I Make Blockbusters at Xiaomi," which explain Xiaomi's industrial chain logic, the 80% logic is mentioned: the new generation of products should maintain 80% of the original functionality and provide 10%-20% of changes, which will greatly increase the repurchase rate and retention rate.

This also means that Xiaomi's products are destined not to pursue extreme technological innovation and change like Sony, but the 80% selected are often the most practical functions for mass consumers.

The benefits of doing so are not only to expand sales. Most products can also save more costs by abandoning the pursuit of extreme innovation. For example, among the four enterprises in the Mijia industrial chain in the above chart, three have seen a slow increase in their gross sales margins.

At the same time, the saved costs can be used to refine the practicality of iterative products, thereby compensating for the poor reputation of first-generation products. Xiaomi obtains the most authentic market demand through pioneer products, compensates early adopters' consumption experience with industrial design, and then occupies the minds of mass consumers through iterative products.

Lei Jun may be the originator of the "small orders, quick response" sales model.

03

Focused Efforts: Spend Money Wisely

Besides relying on modern industrial design and rapid iteration, the final step of Xiaomi's blockbuster methodology is focused efforts, which means having both gains and losses.

When Xiaomi first ventured into the IoT business, it was playfully called a "Xiaomi general store" by Xiaomi fans, selling everything from color TVs and refrigerators to towels and toothbrushes, with a messy and unordered SKU.

However, if we refine the racetracks according to different product lines, we will find that Xiaomi implements a strategy of few products/single products in most fields (except for mobile phones).

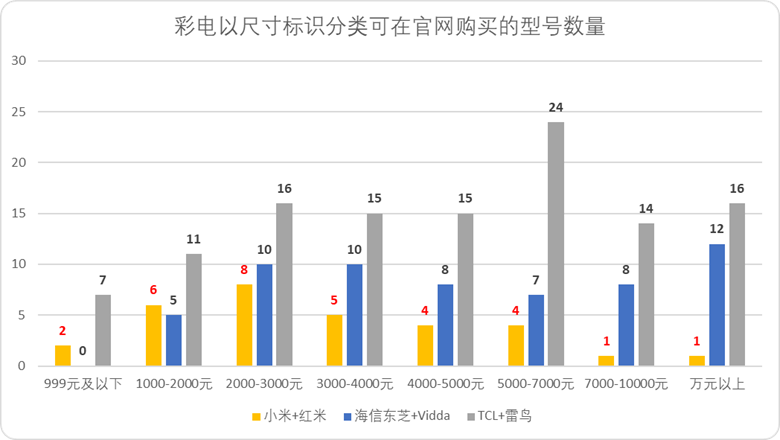

For example, since the launch of Xiaomi TV 1 in 2013, Xiaomi has been relatively restrained in different price ranges. Judging from the models sold by current top TV brands, Xiaomi has the fewest models sold in almost all price ranges.

Image: Number of products sold by different TV brands, Source: Taobao APP

There are three benefits to this restraint:

Firstly, on the demand side, it greatly reduces the time and cost of purchase decisions for consumers. As mentioned earlier in the "Sony faction" logic, the needs of most consumers are not so detailed as to obsess over product parameters like nanometers. Too many product categories can affect consumers' decision-making time.

Moreover, from the perspective of price range distribution, Xiaomi's products tend to follow a normal distribution. The 80% functional demand selection logic mentioned earlier is also accompanied by the 80% consumer logic revealed in "Xiaomi Ecological Chain Battlefield Notes," which is to actively abandon long-tail consumers and leverage price range and functional selection to find the greatest common divisor, using a more concentrated price range of products to leverage greater demand.

Secondly, on the channel side, Xiaomi, which originated in the Internet era, clearly recognizes the importance of information simplification in search mode. Traditional e-commerce search box banners have no more than five pages. If product coverage is too extensive, it will naturally waste more marketing expenses and fail to reach consumers.

Finally, on the supply side, it is difficult to say that fewer models can guarantee that Xiaomi's product quality exceeds that of its peers (which is obviously inconsistent with the actual situation), but it can definitely reduce investment on the cost side. If Xiaomi follows Lei Jun's principle of not exceeding a 5% profit margin for hardware, then Xiaomi's products will definitely be priced lower than competitors, thereby attracting more users.

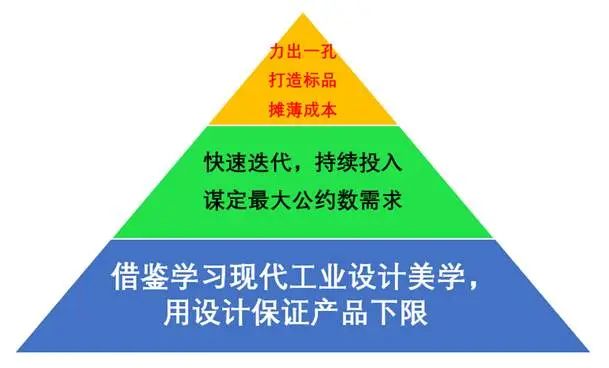

By now, we have roughly sorted out Xiaomi's blockbuster methodology. Xiaomi's differentiated revolution designed around IoT is more like a pyramid structure:

· By drawing on European and American product design aesthetics to form a modern industrial design language, it establishes the lower limit of products and satisfies the aesthetic cognition of new-generation consumers.

· By rapidly iterating to determine 80% of demand and satisfy the greatest common divisor, it allows consumers to clearly see where every penny is spent, forming a basic cognition of "at least not losing," which is also the central value of Xiaomi's products.

· By following the logic of focused efforts, it accurately targets 80% of users and reduces costs through a strategy of few products, which can reduce inventory and save marketing expenses. Ultimately, it creates so-called standard and blockbuster products through the coordination of supply, channels, and demand on three sides.

In addition to IoT, Xiaomi has also replicated this model into more product lines. Even the current popular SU7 and YU7 adopt the same strategy: drawing on advanced industrial design aesthetics from Europe and the United States to ensure a baseline quality, launching products that meet the needs of the mass market, not pursuing the 20% of technological innovation, reducing the number of model launches, and focusing on cost reduction to achieve rapid profitability.

Of course, many companies have attempted to imitate Xiaomi's hit product model over the past few years, but few have succeeded. The reason why Xiaomi can replicate this model across various categories lies in the interaction between the "new retail model" and "high-end product methodology" mentioned by Lei Jun, as well as the core of the "Xiaomi methodology" - stronger execution and organizational capabilities.

As a model enterprise in China's advanced manufacturing sector, our research on Xiaomi will not stop here. We will continue to systematically study this "Xiaomi methodology" in the future to learn the underlying thinking of outstanding entrepreneurs.