From “Her” to “Us”: Didi Takes a Challenging Path

![]() 12/18 2025

12/18 2025

![]() 509

509

Behind the data lies a paradigm shift from physical segregation to preference matching.

Written by | New Business Horizon Yu Weilin

French philosopher Henri Lefebvre once said, “Space is not just a physical container but a social product. It is shaped by social relations and, in turn, shapes them.”

How a nation utilizes its public spaces is a symbol of its level of civilization; how a company manages services within its spaces reflects its respect for users.

However, creating exclusive “her spaces” has always been challenging. From the proposed but repeatedly abolished women-only train carriages in Britain in 1874 to the controversial “female-only parking spaces” in South Korea, these well-intentioned attempts often fall into a vicious cycle: they spark new social controversies due to “segregation” and “labeling,” making it difficult to gain widespread support.

Advances in technology are providing new keys to break this cycle. The latest evidence comes from Didi Chuxing: In August 2024, after multiple surveys and public consultations, Didi launched a beta test allowing female passengers to choose female drivers. Over more than a year, 49% of the female passengers who participated became repeat users, with their satisfaction rate 21% higher than that of other passengers.

Behind the data lies a paradigm shift from physical segregation to preference matching. If women-only train carriages attempted to provide protection by designating “safe enclaves,” ride-hailing platforms achieve this through precise matching, internalizing demand as an optional feature.

Choice implies respect.

Now, Didi has upgraded this feature to the “Female-Friendly Initiative,” offering more choices and protections for both passengers and drivers while striving to optimize services and promote female employment.

However, past experiences tell us that this is not an easy path. Structural challenges in supply-demand matching and implicit expectations for service standards may lead to overinterpretation in public opinion. What is Didi’s core purpose behind this repeated refinement and tested public space practice?

What Does “Female-Friendly” Mean?

Didi’s “Female-Friendly Initiative” began with two large-scale “listening sessions.”

In July 2024, during a public consultation involving 75,000 netizens, the option for “female passengers to choose female drivers” received the highest votes, with over 60% of voters endorsing this need. The following month, the beta test for female passengers to “choose female drivers” began.

On the eve of International Women’s Day 2025, a survey aimed at understanding the living conditions of female drivers revealed that 70.9% of female drivers explicitly stated, “We hope to serve more female passengers,” demanding an expansion of the “choose female drivers” pilot. Subsequently, Didi invited drivers, passengers, media, and scholars to an open day for collecting opinions, brainstorming ideas for the upcoming upgraded Female-Friendly Initiative.

These two service iterations share a common core keyword: peace of mind—for both drivers and passengers.

On the user side, many female passengers describe Didi’s service as “dreams coming true.” Netizen Xiaoyun recounted, “There were times when I had to travel late at night to remote areas without subway access. Once, at 11:30 PM, I hailed a ride with a nearly dead phone battery. I was really panicked, wishing a female driver would pick me up.”

Data shows that orders using the “choose female drivers” option are concentrated during late nights, in remote suburbs, at transportation hubs, and for trips with children. To date, a cumulative 600,000 verified female passengers have used this service, with 49% being repeat users, 46% occasional users, and 50% of surveyed users stating they would actively recommend it to friends and family.

On the other hand, true “female-friendliness” is never a “single win.” Feedback from the driver side shows that female drivers’ satisfaction with such orders is 12% higher than with regular orders, their willingness to accept orders increases by 17%, and their sense of security improves by 14%. Some female drivers even prepare masks, sanitary pads, and plum candy for female passengers.

“This approach protects both female passengers and female drivers. Completing a trip with a girl feels like a ‘sisters’ outing,’” a female driver shared on social media.

For female drivers, a sense of security exists not only in driving scenarios but also in the support and recognition behind them. According to the “2025 DiDi Digital Mobility Female Ecosystem Report,” as of 2024, over 1.05 million female drivers in China have earned income through Didi, with 83.4% reporting improved living conditions and capabilities; 64.3% have made other female friends while driving, enhancing both professional identity (professional identity) and social connections.

However, starting from “seeing needs,” why were past “women-only train carriages” criticized, while Didi’s Female-Friendly Initiative has gained more recognition? The second keyword behind this is: choice.

Traditional women-only train carriages represent an exclusive form of “spatial segregation,” which can waste resources during peak transportation times and trigger social backlash due to forced categorization. Didi’s solution, however, is an adjustable form of “preference matching,” whose underlying logic is to empower both passengers and drivers with choice through technological means.

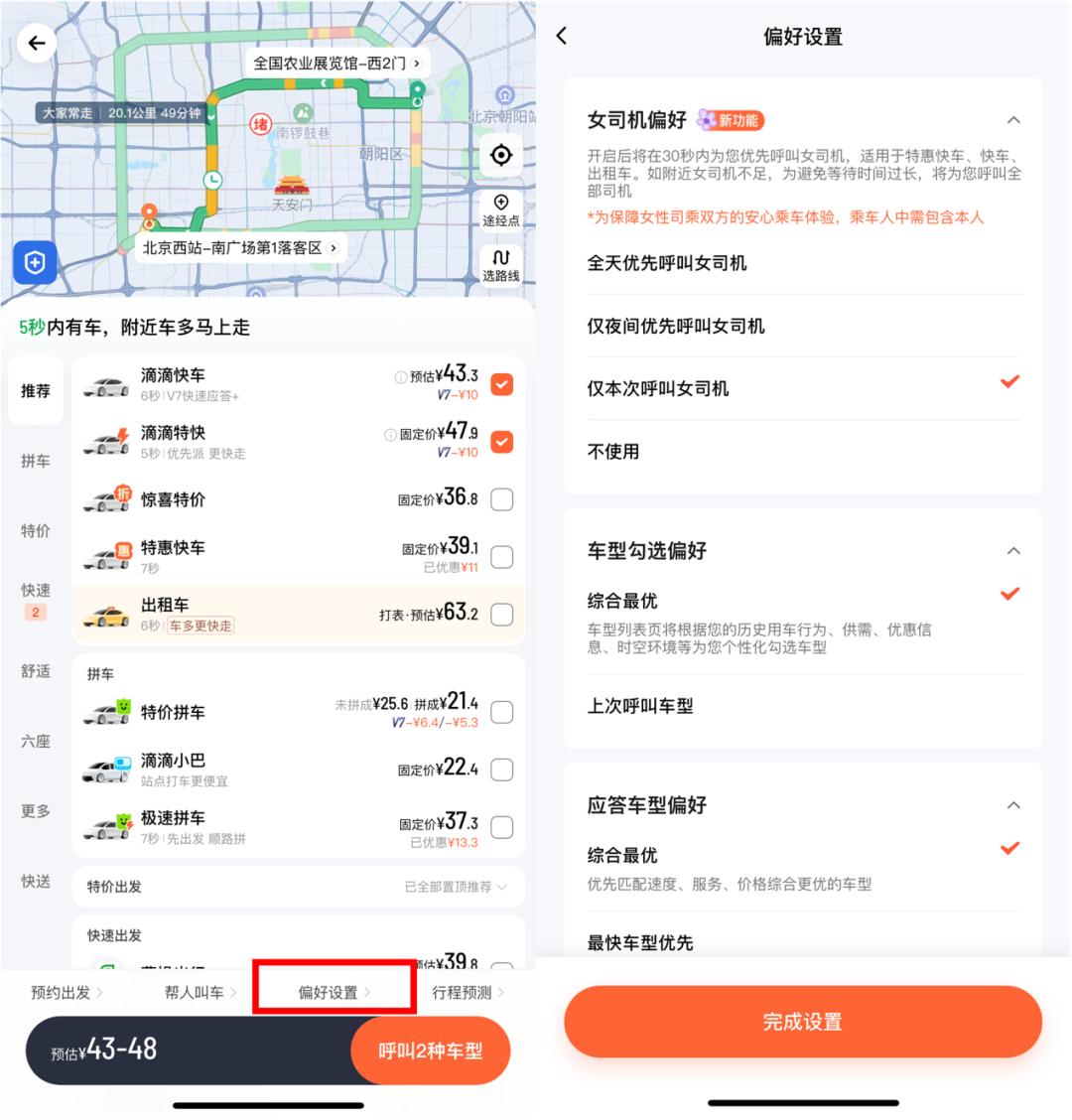

From version 1.0, where female passengers could “choose female drivers,” to version 2.0, where female passengers can freely switch between “all day, nighttime, this trip only, or not use,” and female drivers can independently decide to “join or exit” the priority queue. The platform also sets a 30-second priority matching window, expanding the call range if no match is found within that time. This means the protection strategy has evolved from “designating safe enclaves” to “offering priority options.”

This also reflects the conceptual evolution of our times. True equality does not ignore differences but provides diverse, optional solutions based on acknowledging them. During version 1.0, many doubts arose online, with men questioning “reverse discrimination,” male drivers worrying about reduced orders, and female drivers feeling there might be more friction among women.

Version 2.0 has functionally avoided these issues as much as possible, returning choice to both passengers and drivers while seeking the “greatest common denominator” dynamically. As the Beijing News commented, “Any new feature or service innovation inevitably involves balancing diverse interests and values. Simply resorting to binary distinctions or gender opposition is not only biased but also creates unnecessary resistance to implementation.”

Both data and facts sufficiently demonstrate that Didi has found a difficult yet correct path in exploring solutions tailored to Chinese users’ habits.

The “Curb Ramp Effect” in the Digital Age

The “Female-Friendly Initiative” targets female passengers and drivers but is not solely for them. In tackling the challenging task of creating “her spaces,” the platform capabilities developed can be seamlessly extended to more niche groups in need.

The most typical example is the “preference matching” capability, which transforms vague, psychological needs for safety and comfort into quantifiable preference settings within product logic. Through iterations, Didi has established a complete closed loop: users can set preferences autonomously, the system intelligently matches them (with a 30-second priority window), and global efficiency is maintained (expanding the call range if no match is found within the window).

This capability, evolving from standardized vehicle supply to personalized demand fulfillment, can be applied to countless scenarios. For instance, in senior mobility, elderly individuals who are less proficient with smartphones and more anxious about route changes can be prioritized for experienced, patient drivers through preference matching. For medical trips, patients and families needing nighttime hospital visits can have a “medical priority dispatch” preference developed, matching them with drivers familiar with hospital routes, whose vehicles have cleaner interiors, or offering “scheduled ride” guarantees.

In fact, over the past few years, Didi has focused on exploring personalized needs for all users, launching services such as senior mobility, accessible travel, youth protection, pet travel, charter services, and overseas travel.

For example, in pet travel, addressing the difficulty pet owners face when hailing rides with pets, the pet express service allows drivers to choose whether to accept such orders, while passengers must label their pet information. This avoids a one-size-fits-all approach and maintains vehicle cleanliness, aligning with the flexible mindset of “female drivers independently choosing whether to prioritize such orders.”

Didi’s support and incentives for female drivers, including exclusive critical illness benefits covering breast cancer, cervical cancer, and other female-prevalent diseases, as well as in-car alarm alerts, safety hotlines, drunk passenger reporting functions, and organizing badminton tournaments, baking, and flower arrangement activities on International Women’s Day and Mother’s Day to build exclusive communities—all provide social empowerment support for platform drivers, enhancing their professional identity.

These service practices recall the “curb ramp effect” in sociology—initially built to facilitate wheelchair access for disabled individuals at the junction of sidewalks and roadways, these “curb ramps” inadvertently benefit parents pushing strollers, travelers pulling luggage, and cyclists. When we create conditions for those in need, society as a whole ultimately benefits.

In other words, the “Female-Friendly Initiative” is not merely a service innovation but a crucial infrastructure for capabilities. It demonstrates that, empowered by digital technology, enterprises can pursue commercial efficiency while breaking down various tangible or intangible “curbs” through refined operations and systematic empowerment, ultimately leading to a more inclusive and civilized common space.

From “Scale Efficiency” to “Exceptional Service”

Ride-hailing platforms have transitioned from an era of extensive growth and market expansion to an era of refined infrastructure. Two questions must be addressed: First, as the incremental market shifts to a stock market, how can user retention and experience be ensured? Second, with more drivers engaging in long-term employment, how can they be better served and regulated?

Looking back, Didi’s Female-Friendly Initiative represents an inevitable progression for enterprises, industries, and society.

As the market gradually standardizes, the core of competition in the ride-hailing industry has shifted to user retention, experience enhancement, and brand loyalty building. The “Female-Friendly Initiative” serves as a critical entry point for this strategic shift, directly addressing long-standing but unmet experience needs in ride-hailing services. Meeting niche demands determines whether user stickiness can be increased and new growth engines can be leveraged in the stock era.

In July 2025, Uber followed suit, announcing a pilot program in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Detroit to support female passengers choosing female drivers.

To some extent, this replicates the bidirectional preference model validated by Didi in China’s complex scenarios. This reverse output underscores Didi’s grasp of the new round of competitive core.

From a societal perspective, Didi has evolved from an efficient mobility transaction platform into an intelligent mobility infrastructure and friendly service ecosystem. Its mission has shifted from providing standardized products to offering personalized, precise matching for diverse groups.

Facing a driver community of over ten million, the platform needs to provide a sense of “belonging.” As female driver Zhang Zuxia, who received the “Female Pioneer Award” at a recent Didi Driver Festival, said, “I used to think driving was just a livelihood until I stood on the podium and heard my story being told. Only then did I realize this job could also be respected and seen.”

Facing a vast user base, the platform needs to provide safety and comfort. This means recognizing and respecting diverse needs, whether it’s the safety anxieties of women traveling at night, the digital divide elderly individuals face with smart devices, or the barrier-free travel needs of disabled individuals. These are all “long-tail demands” far beyond what standardized services can cover. How seriously they are addressed determines Didi’s fundamental position in the next decade.

Therefore, rather than saying Didi’s pursuit of “her spaces” is taking a difficult path, it is more accurate to say it is a necessary journey from commercial value to social value.

From here, the platform no longer pursues maximizing efficiency in transporting passengers from point A to point B but strives to make every trip carry more respect and warmth. Is this not, as an industry leader, a fitting answer to the future of mobility?