Enhancing AI Cooperation and Sensibility: A New Research Perspective on Guilt

![]() 08/05 2025

08/05 2025

![]() 439

439

Amidst the rapid advancements in AI, a pivotal question arises: How can we align AI with human interests? This query is not about enhancing AI's intelligence but rather its "sensibility."

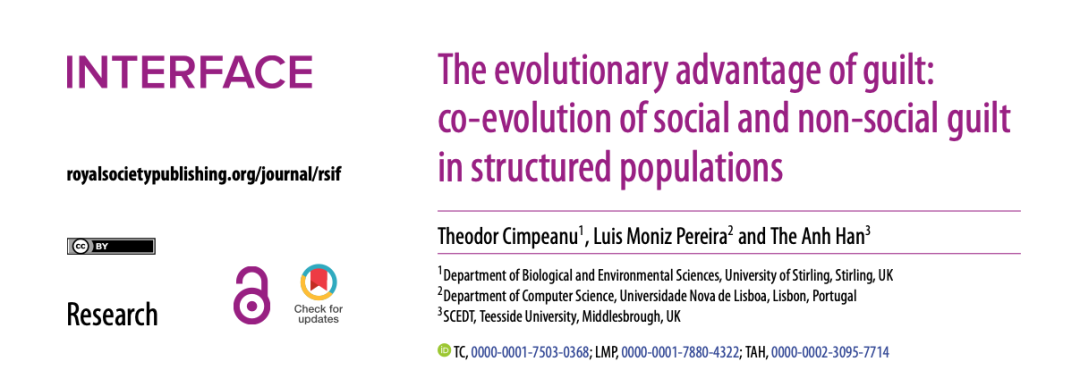

A recent study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface offers an intriguing approach:

Instead of teaching AI all the rules, we could simply make it "feel like it has done something wrong" – instill a sense of "guilt" – which may foster greater cooperation and controllability.

While this sounds psychological, it's grounded in game theory.

1. Guilt: A New Key to AI Training

Humans build society not just through laws and institutions but also through deep emotional mechanisms like shame, repentance, and morality. These emotions encourage self-restraint and discourage selfishness.

What if AI possessed this "self-restraint" ability?

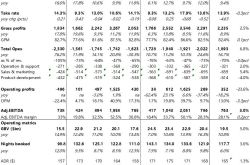

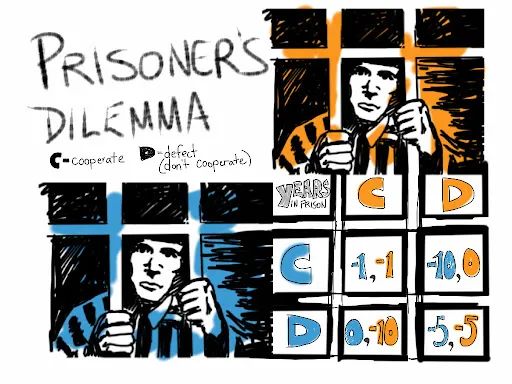

The research team designed a "Prisoner's Dilemma" game experiment for AI agents. In this classic game-theoretic framework, each agent must choose to cooperate or betray, and the optimal group outcome hinges on mutual trust and long-term strategies.

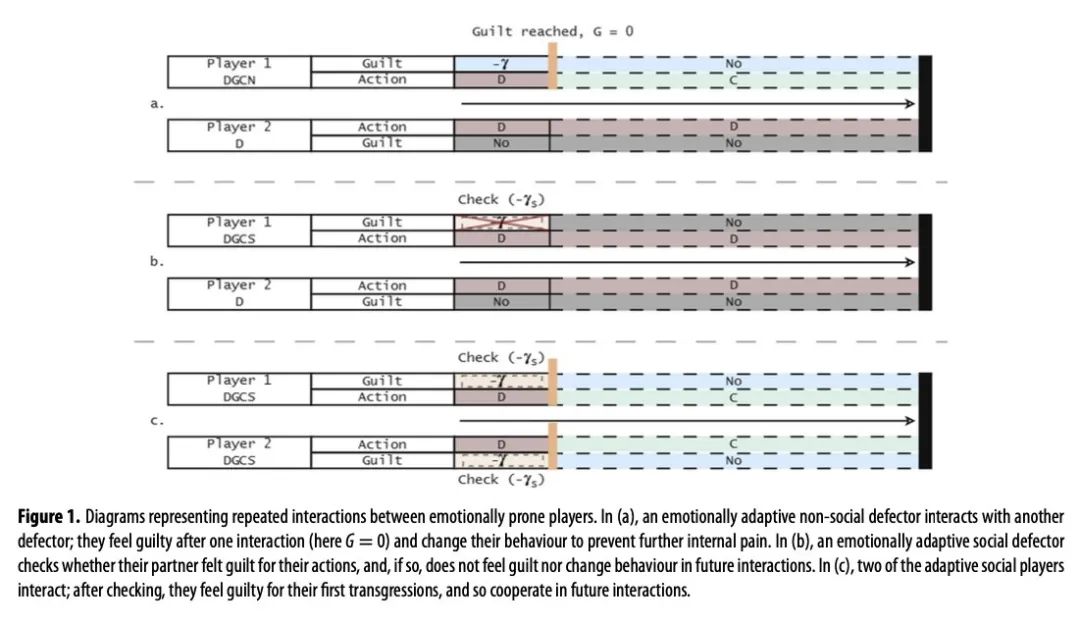

To test the role of "guilt," researchers added two mechanisms:

Social Guilt: The AI adjusts its behavior if it knows its opponent will also feel guilty about similar actions.

Non-social Guilt: Regardless of the opponent, the AI automatically corrects its behavior when it deviates from cooperation.

These AIs "resolve" their guilt based on behavioral points. For instance, if they betray too often, they sacrifice points in the next round to "compensate" for past non-cooperation.

2. Evolutionary Game Theory: Cooperation Is More Complex Than You Think

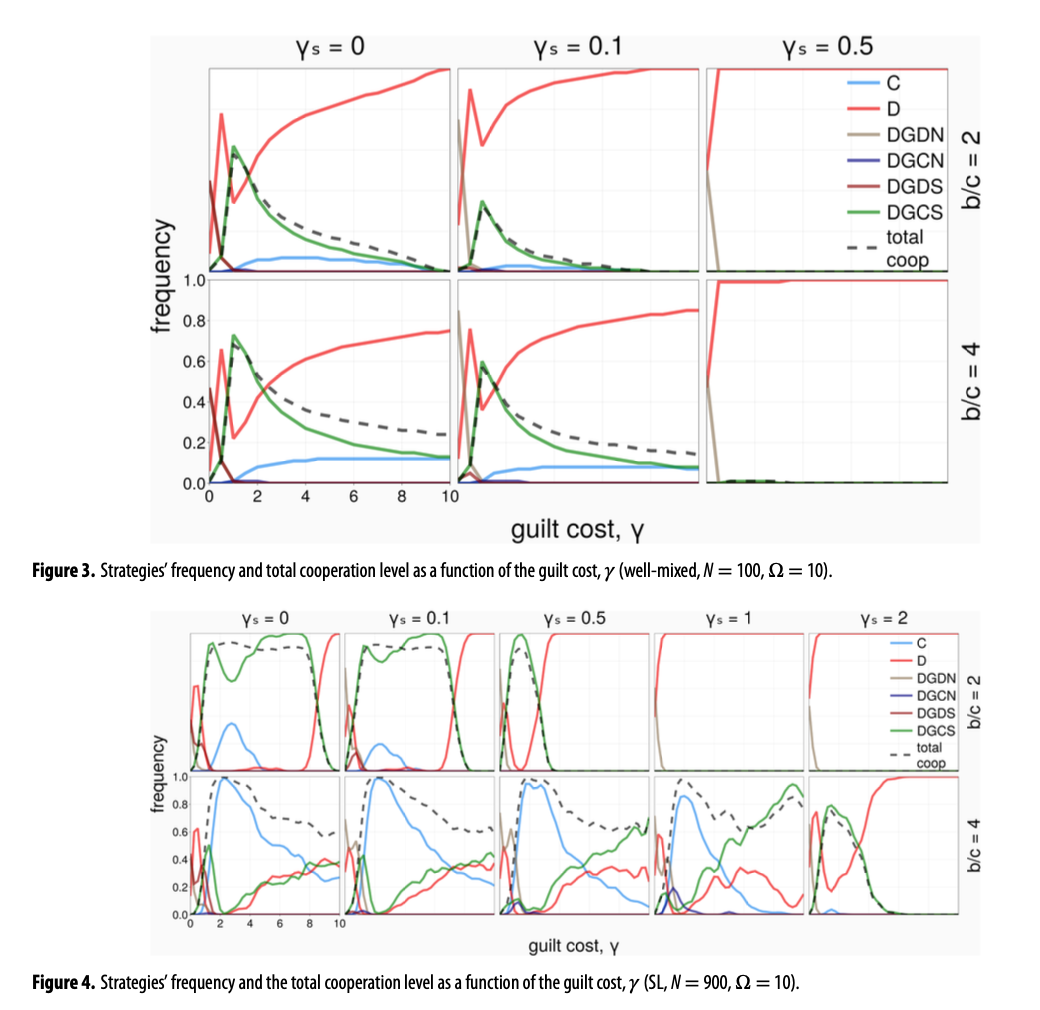

In the experiment, AI agents played games continuously and learned from each other's strategies, evolving towards higher-scoring behaviors. This setting mimics a simplified evolutionary process.

The results were fascinating:

AIs with "social guilt" were more likely to form cooperative relationships and performed better overall.

While "non-social guilt" had average effects, it could survive long-term in specific network structures.

In fully connected networks, the non-social mechanism was quickly eliminated.

However, in "local structures" resembling social circles, the guilt mechanism was more stable.

This indicates that in environments closer to human social structures, AI may exhibit more coordinated behaviors through "soft constraints."

3. Do We Really Need to Give AI Emotions?

This research isn't about endowing AI with true emotions but about simulating emotional behavioral effects through mechanisms.

The core idea is that emotions aren't useless byproducts but efficient evolutionary coordination tools. If AI must collaborate closely with humans and other AIs, making it "know what's wrong" and "willing to change" might be more effective than merely setting punishment rules.

Moreover, this mechanism can be quantified and controlled, offering greater stability than human emotions.

4. How Close Are We to Reality?

Current experiments are basic, using simple decision-making agent systems and not validated on more complex multimodal AIs.

However, the potential of this direction cannot be overlooked.

AI capabilities are rapidly expanding, from coding and drawing to video generation and organization management. They're becoming integral to complex societies. If we hope these systems integrate into the human environment as reliable partners rather than threats, we must consider not just making them "understand the goal" but also "understand the consequences."

In this context, guilt isn't a sign of weakness but an extension of rationality.

AI development was once about intelligence; now it's about boundaries; and in the future, it may be about reflection.

We don't expect AI to be saints, but if it can "take a step back" at critical moments and make choices from an overall perspective, that could be a step towards "trustworthy AI."