J.P. Morgan Calculates the Cost of AI Investment: Each iPhone User Must Pay an Extra 250 Yuan Monthly to Break Even

![]() 11/17 2025

11/17 2025

![]() 455

455

On November 10, J.P. Morgan published a landmark research report on the AI industry, offering readers a meticulous, almost “anatomical” breakdown of the current industry landscape:

It covers everything from the progress of U.S. data center construction and the strain on power systems, to tech giants’ capital expenditures, financing sources, and debt structures, all the way down to the logic of industry commercialization and economic feasibility.

This is an exceptionally data-rich, comprehensive foundational study that essentially addresses the market's most pressing questions, making it worthy of in-depth, repeated study.

Several particularly noteworthy conclusions from the report:

1) U.S. data center construction is expanding beyond tech giants to include a broader range of enterprises. This wave of construction is almost single-handedly propping up this year’s non-residential construction investment in the U.S. Excluding data centers, non-residential construction has actually seen negative growth this year, indicating that AI infrastructure has become a cornerstone of the U.S. economy.

2) While over 300 gigawatts of data center capacity are planned nationwide, J.P. Morgan estimates that only 175–200 gigawatts can be realistically achieved. Even so, 18–20 gigawatts will be added annually over the next decade—more than five times the historical average of 4 gigawatts.

3) From September 2024 to 2025, over 100 gigawatts of new power generation projects are queued for grid connection in the U.S., with natural gas remaining the dominant energy source. Its planned capacity surged 158% year-on-year to 147 gigawatts, reflecting that power supply has become the primary bottleneck for AI expansion.

4) Despite staggering cash reserves, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and others are experiencing shrinking free cash flow due to sustained double-digit growth in capital expenditures, forcing them to shift from “self-funding” to “borrowing for AI.” Meanwhile, securitized financing related to data centers is rapidly rising, becoming a new infrastructure financing channel.

5) More critically, J.P. Morgan calculates that to achieve a reasonable 10% return on investment (ROI) for AI infrastructure, the industry must generate approximately $650 billion in annual revenue, equivalent to 0.6% of global GDP. In practical terms, this equates to each iPhone user paying $35 more monthly and $420 more annually.

For reference, global iOS users averaged just $10.4 in monthly app spending last year—achieving this revenue target requires AI monetization to improve more than threefold from current levels.

/ 01 /

AI Infrastructure Becomes the “Pillar” of U.S. Economic Growth

Historically, data centers’ power capacity was measured in megawatts (MW); now, the industry increasingly uses gigawatts (GW). One gigawatt equals 1,000 megawatts, and this unit shift alone signals that data centers are entering an era of “thousandfold” expansion.

Annual newly added installed capacity (new installed capacity) historically hovered around 2 gigawatts. But with the AI boom, growth surged: doubling in 2024, doubling again in 2025, and potentially exceeding 10 gigawatts in 2026.

Some companies have disclosed over 70% year-on-year GPU order growth, indicating the industry is entering a high-growth cycle.

Equipment supplier Vertiv’s forecast confirms this trend: from 2025 to 2029, global installed capacity will grow by approximately 100 gigawatts. Prior to the AI boom, global data center capacity totaled just 50 gigawatts, meaning the industry will double its past capacity in five years.

So, who is driving this massive data center construction wave?

Current expansion remains dominated by the cloud computing trio (AWS, Microsoft, and Google), but new players are rapidly joining. Over the past year, non-giant firms have secured projects accounting for roughly a quarter of the market share.

The number of participants is growing exponentially. To date, about 65 companies have projects exceeding 1 gigawatt in the pipeline, up from 23 last year, with nearly 200 enterprises actively advancing data center businesses.

J.P. Morgan estimates these investments support approximately 19,000 to 20,000 EFLOPS (exaFLOPS) of GPU computing power, compared to just 2,000 EFLOPS globally in 2023. Computing power has expanded nearly 10-fold in just two years.

How are these data center construction projects progressing?

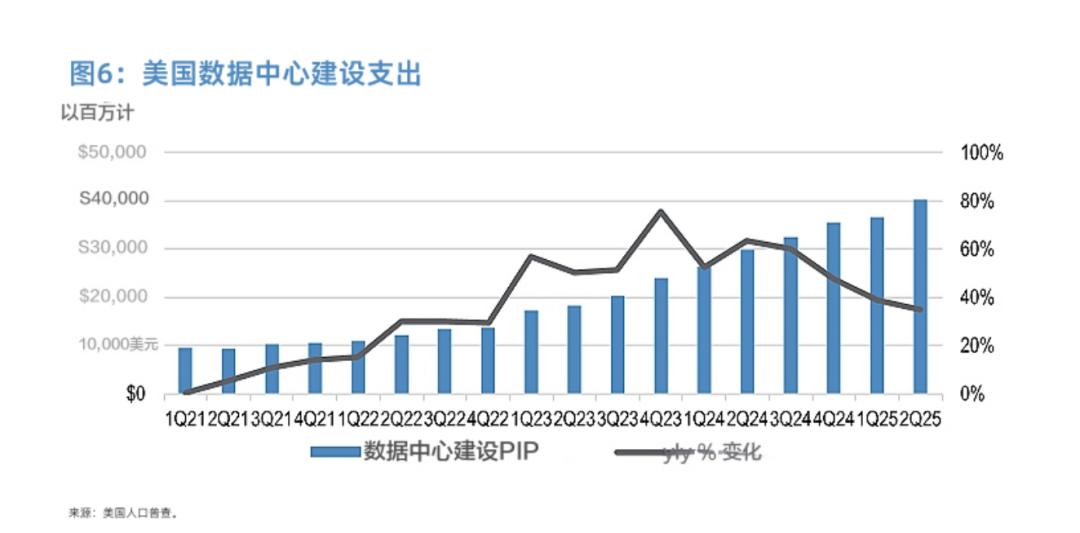

The U.S. Census Bureau now independently tracks “data center spending.” Latest data shows data centers continue to drive U.S. non-residential construction investment. While not the largest spending category, they account for 6% of total non-residential construction, with significant future growth potential.

Manufacturing spending is five times higher, but excluding data centers, U.S. non-residential construction investment has actually declined this year. Thus, data centers have become virtually the only sector expanding against the trend.

To further validate trends, J.P. Morgan established a tracking system in January 2023. To date, U.S. data center projects in planning or progress total over 315 gigawatts, with 165 gigawatts added in Q1 2025 alone. A year ago, the figure was around 130 gigawatts, and by late 2022, U.S. AI-related installed capacity was just 20 gigawatts.

From a completion standpoint, however, the outlook is less optimistic. Of the 600+ data center projects tracked, only a handful are fully built and operational.

Currently, U.S. data centers under construction total approximately 25 gigawatts. While potential planned capacity exceeds 300 gigawatts, this assumes all remaining land can be developed—an unrealistic premise.

Considering site selection, grid constraints, environmental regulations, and equipment supply chains, a more credible planning range is 175–200 gigawatts. Even at this conservative estimate, annual capacity additions will still exceed 18–20 gigawatts over the next decade, more than five times the past average of 4 gigawatts.

The greater constraint lies in supply, not demand. The current U.S. power grid cannot support 300 gigawatts of data centers operating simultaneously; power infrastructure has become the critical bottleneck for industry expansion.

/ 02 /

Demand Doubles, but Power Supply Falls Short

The number of U.S. data centers is surging, but the power system cannot keep pace.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory projects that by 2028, U.S. data center annual electricity consumption could soar from 175 TWh to 325–580 TWh.

To meet this demand, the U.S. must add at least 100 gigawatts of generation capacity; otherwise, many newly built data centers will face “completion without operation” risks.

The issue is that new power capacity cannot be deployed overnight. Natural gas plants take 3–4 years from order to delivery, while new nuclear plants often require over a decade and frequently exceed budgets.

Consequently, more tech giants are considering “build your own generation” (BYOG) solutions, but these face lengthy approval processes, construction timelines, and upfront capital requirements.

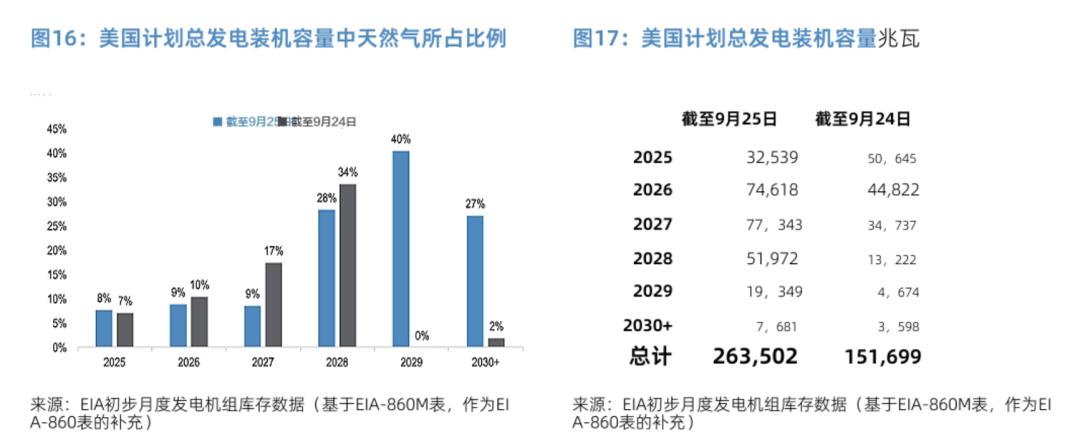

Numerous power projects will come online in the coming years. Between September 2024 and 2025 alone, over 100 gigawatts of new generation capacity are queued for grid connection, with natural gas remaining dominant due to its cost, stability, and scalability.

Natural gas planned capacity has surged 158% year-on-year to 147 gigawatts. Renewables top the grid connection queue, but many projects aim solely for tax incentives, with few achieving rapid commissioning. More promising technologies like nuclear and energy storage have seen virtually no new projects in recent years, offering no short-term relief.

Critically, even excluding AI data centers, U.S. electricity demand has steadily risen.

Increased household appliances, accelerating EV adoption, and growing electrification of commercial and industrial buildings have maintained U.S. electricity demand growth at around 1% annually over the past decade. Now, AI data centers alone could double this growth rate to 2% or higher.

However, due to prolonged low electricity prices in recent years, compounded by the pandemic and supply chain disruptions, many utilities have been cautious about investing in new power plants, creating a significant supply lag.

U.S. residential electricity prices have risen substantially in recent years, sparking concerns that data centers are “stealing” power from households.

Regulators are now focusing on two key issues:

First, ordinary users must not subsidize data centers. Thus, data center power purchase agreements (PPAs) typically include steep penalty clauses to prevent cost shifting to residents if companies exit early.

Second, “privileged pricing” must be avoided. Most data centers now adopt “behind-the-meter” purchasing models, buying directly from the grid like ordinary users without exploiting preferential policies.

Nationwide, residential electricity costs as a share of income remain manageable. However, in states with already high electricity prices (e.g., California, New Jersey), the burden is significant, prompting regulators to scrutinize the relationship between data center expansion and local electricity costs.

/ 03 /

Tech Giants Enter the “Debt Financing” Era, with Oracle Facing the Greatest Pressure

The AI boom has accelerated data center and computing power investments to unprecedented levels: global data center capital expenditures have surged to $450 billion annually.

Despite robust cash flows, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Oracle, and other tech giants face shrinking free cash flow due to sustained double-digit capital expenditure growth, forcing them to shift from “self-funding” to debt financing:

Oracle issued $18 billion in bonds in September; Meta completed a record $30 billion debt offering; Alphabet has issued $36 billion in bonds over the past year, establishing “normalized” financing rhythms in euro and dollar markets.

These funds almost entirely support massive investments in AI chips, data centers, power, servers, and other areas.

With approximately $100 billion in cash and a very low debt ratio, Google maintains a “normalized bond issuance” strategy, raising about $35 billion annually while keeping its balance sheet robust.

Meta has adopted a more aggressive financing approach. Take its recent $27.3 billion Beignet Investor LLC transaction: Blue Owl holds 80% equity in the project, which does not immediately appear on Meta’s balance sheet.

Only when the project enters its lease phase in 2029 will related obligations be reflected in debt metrics. This structure allows Meta to expand more lightly and reduce public market bond issuance frequency.

In contrast, Amazon’s situation is more nuanced. It has the highest capital expenditures, projected to reach $150 billion in 2025, but has not issued new debt in three years. If AI investments continue to rise, Amazon will likely return to the bond market.

Microsoft remains the most “cash-rich” player, with the strongest balance sheet and the least need for debt. Past major acquisitions (e.g., the $75 billion Activision Blizzard deal) were completed in all cash.

Meanwhile, Microsoft is offloading self-construction pressures by investing in third-party infrastructure like CoreWeave and nScale, effectively pursuing “capital-light expansion.”

Oracle undoubtedly faces the greatest pressure. Its debt issues have become structural risks. By Q1 2026, Oracle’s total debt reached $91 billion, and after issuing another $18 billion in September, its debt exceeded $100 billion.

Market demand for these bonds was enthusiastic, with orders totaling $88 billion. J.P. Morgan attributes this to a lack of “AI-themed” investment-grade new debt in the market, rather than Oracle’s superior credit.

While Oracle faces no immediate debt pressure, its maturity profile will rapidly escalate from 2026: $5.75 billion due in 2026 and another $5 billion in 2027.

Combined with high capital expenditures and dividend demands, Oracle will likely become a frequent public debt market participant in the coming years. However, its BBB rating (with a negative outlook) is declining in flexibility.

While these tech giants remain the world’s most sought-after investments, market sentiment is subtly shifting. Meta’s $30 billion bond issuance widened spreads by about 20 basis points, while Oracle’s $18 billion deal saw spreads rise 30–40 basis points, indicating investors are pricing “AI debt” more cautiously.

Meanwhile, structured financing like Beignet is gaining traction. Essentially, it involves “renting self-built data centers” with external private equity funds purchasing assets upfront:

Funds come from institutions like Blue Owl, while Meta keeps its balance sheet light and uses its own data centers via rental payments in the future. This allows tech companies to expand while maintaining credit ratings.

Beyond tech giant financing, securitized issuance for data centers is rapidly climbing.

Year-to-date, related ABS and CMBS issuance has reached $21.2 billion, nearly doubling from last year and accounting for 5% of the total new issuance market. Most deals originate from operational data centers, as mature projects carry lower risks and stable rents, attracting investor confidence.

Currently, securitized financing for projects under construction remains rare, with only one $474 million deal for a 30-megawatt data center in Illinois, carrying significantly higher financing costs than mature projects.

Meanwhile, bond issuance by AI-related firms is surging:

Data center bonds have reached $44 billion this year, 10 times the 2024 volume;

Investment-grade tech enterprise bonds account for 14.5% of the total bond market, matching that of major U.S. banks.

From the current perspective, the market has sufficient funds to “absorb” this wave of AI debt. The U.S. high-yield bond market stands at $1.56 trillion, the leveraged loan market at $1.67 trillion, and private credit management at $1.73 trillion, with an additional $466 billion in idle resources.

In other words, there are at least $5 trillion in “leveraged capital” circulating in the market, actively seeking new assets. AI is highly likely to become the destination for these funds.

/ 04 /

For AI investments to pay off, every Apple user may need to spend an extra $250 per month.

Amid the current AI investment frenzy, there are essentially two highly uncertain risks: the capacity to generate revenue and the potential for technological upheaval.

First and foremost, it's crucial to recognize that AI is no small - scale investment endeavor. The total construction cost of the AI industry could surpass $5 trillion. This figure encompasses not only the expenses for data centers, electricity, and GPUs but also the costs associated with supporting energy infrastructure, land acquisition, cooling systems, and labor.

What truly determines whether an AI project succeeds or fails is whether these substantial investments can be recouped and whether future technological advancements will render current investments obsolete.

History has witnessed similar scenarios. Two decades ago, in the telecommunications sector, companies poured significant amounts of money into building fiber - optic and wireless networks, anticipating long - term growth driven by internet traffic. However, the actual demand grew at a much slower pace than expected. Business models struggled to cover the enormous construction costs, ultimately leading to a bubble burst and the collapse of numerous firms.

This historical episode serves as a valuable lesson: technological revolutions themselves do not guarantee profits; it is the business models that hold the key to financial success.

The same principle applies to AI today. AI data centers can keep being built, but the critical question is: who will foot the bill for this immense computing power? Are consumers willing to shell out dozens of dollars more each month? Can businesses genuinely leverage AI to enhance efficiency and boost their revenues? These questions remain unanswered.

Take Google as a case in point. AI is indeed transforming its core business, search. An increasing number of users are now bypassing traditional search links and directly reading AI - generated answers. This has resulted in a 30 - 40% decline in website traffic that relies on search referrals, a significant impact. However, for Google itself, this shift could be advantageous as it gradually transitions from "recommending search results" to "providing direct answers," which may strengthen user loyalty and enhance its monetization potential.

When it comes to the return on AI investment, JPMorgan Chase conducted a highly insightful sensitivity analysis:

To achieve a reasonable 10% return on investment, the AI industry may need to generate approximately $650 billion in annual revenue, which is equivalent to nearly 0.6% of global GDP.

To put this figure in context: it would be akin to requiring every iPhone user to pay an additional $35 per month, totaling $420 annually; or Netflix subscribers to pay an extra $180 per month, amounting to $2,160 annually.

What does this imply? According to data from an external blog, in 2024, iOS had between 1.46 and 1.8 billion active users, with each user spending $10.4 per month on apps, which is more than triple the original expenditure.

If the return rate rises to 14%, this figure jumps to $53 and $274, respectively.

While we do not anticipate consumers to bear the entire cost burden, the question still lingers: can the efficiency gains from AI currently create such enormous value?

Another risk stems from the potential impact of "extreme leaps in technological efficiency." In January, DeepSeek released its R1 model, claiming performance comparable to that of OpenAI's but at a lower cost.

Upon this announcement, NVIDIA's market value instantly plummeted by $600 billion. Such sudden technological breakthroughs force the market to re - evaluate the cost structure and leading positions within the AI industry.

If a company can truly offer the same computing power at a lower cost, the commercial value of existing investments may be re - assessed, potentially leading to a "paradigm shift."

Currently, numerous small and medium - sized companies are actively participating in AI infrastructure construction. For example, firms like WULF and Cipher finance the construction of AI data centers through bond issuance and then lease computing power to major clients such as Google. One notable characteristic of these projects is that

risks are underwritten by large corporations (e.g., Google's commitment to pay rent), which makes them seem more stable. However, such models may also inflate market optimism about future AI demand. If subsequent monetization efforts fall short of expectations, smaller companies could be the first to face difficulties.

Of course, if the industry's overall revenue fails to meet projections, another scenario could emerge: a winner - takes - all dynamic. A few companies with genuine technological, capital, and ecological advantages may rise to the top as leaders, while the rest may struggle to survive.