AI Entrepreneurship: Trapped in the Collective Illusion of 'Chasing the Fastest ARR'

![]() 11/17 2025

11/17 2025

![]() 406

406

In the AI era, everyone has a question: What constitutes a company's moat?

Not long ago, Bryan Kim, a partner at a16z, proposed an impressive viewpoint: Momentum is the moat for AI products.

His reasoning is that growth is so crucial because the AI era is evolving too rapidly. Only by being the first to win over users' minds can you build more traditional 'moats' in terms of product, distribution, and other aspects.

Of course, not everyone agrees with this viewpoint.

Not long ago, Kyle Harrison, a partner at Contrary Venture Capital, wrote that Bryan's idea is somewhat similar to Elon Musk's. Musk once said, 'Moats are useless; that's an old-school approach. If your only way to defend against competition is a moat, you'll eventually be surpassed. What truly matters is the speed of innovation.'

However, the key difference lies here: The 'momentum' emphasized by the former refers more to revenue growth, especially the growth rate of annual recurring revenue (ARR). He views rapid growth as the most critical signal in a company's early stages.

The problem is that when people focus too much on 'how fast you grow,' some inherent issues in the venture capital system are amplified: Companies are pressured to take shortcuts, neglect long-term development, and only pursue short-term, impressive numbers.

Below is the original article written by Kyle Harrison:

/ 01 /

When Capital Only Chases the 'Top 5%', the Startup Ecosystem Held Hostage by Myth

This is the classic 'to a man with a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.' Whether it's Bryan's 'unless you can grow your annual recurring revenue from $0 to $2 million in 10 days, I'm not interested' or Hemant's 'tripling growth is outdated. You need to go from $1 million to $20 million to $100 million to be interesting,' both reflect this mindset.

This is the mentality of those managing billion-dollar funds. They need the largest possible returns, so every company should aim for the largest possible returns to be considered interesting.

I've always believed that there's no absolutely correct way to start a business. Every founder has their own path, and as long as it's legal and compliant, there's no issue.

But what worries me is that many people are using the wrong approach—holding a hammer and seeing everything as a nail. This way may limit the growth of the next generation of companies, making it difficult for them to break through scaling bottlenecks and remain stuck at a 'medium size' rather than growing into truly influential billion-dollar companies.

You could say 'aim for the moon; maybe you'll hit the stars,' but the reality is that the way you build a company largely determines how far it can go.

Taking a company from $1 million to $20 million to $100 million is almost impossible through 'steady progress.' You need to be more aggressive and efficient in every aspect, including pricing, marketing, hiring, and R&D. Except for a few rare exceptions that can achieve massive scale with very few people, most companies aiming for rapid growth often resort to an unsustainable, high-pressure growth model.

For example, Wealthfront has been around for 17 years and now generates $308 million in revenue with a net profit of $123 million. Achieving this is already outstanding for a company. However, in the eyes of some large venture capitalists, such results are 'not good enough'—they pursue 'super unicorns' that can reach $10 billion or $100 billion in market value.

Here lies the problem. In reality, among all publicly traded companies, less than 5% have a market value exceeding $10 billion, and those exceeding $100 billion are even rarer. In other words, venture capitalists are only chasing the top 5% of extreme successes while ignoring the 95% of robust (stable), profitable companies that create long-term value.

When this mindset dominates the market, entrepreneurs start to imitate, and investors follow suit, ultimately holding the ecosystem hostage to the 'top company myth.'

Meanwhile, companies that could create good products, support their teams, benefit employees, and satisfy customers—the very companies that sustain the economic 'middle class'—are pushed off the stage.

/ 02 /

Competition Is for Fools

The irony of 'momentum is the only moat' is that the so-called 'momentum' is often an anti-moat.

Peter Thiel famously said in 'Zero to One,' 'Competition is for losers.'

Tolstoy wrote, 'All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.' In the business world, the opposite is true—every successful company has its unique path to success, achieving monopoly status by solving a problem no one else has; while failing companies are strikingly similar: they are all trapped in competition.

Today, many chasing 'momentum' are engaging in this futile competition. Almost every week, you hear about a company achieving 'millions in ARR (annual recurring revenue) in a few months,' which sounds exciting and immediately attracts a horde of imitators.

As a result, everyone starts flocking to the same track ( track : track/field): legal AI, AI code generation, AI writing, AI integration, AI orchestration... In every direction, companies emerge claiming to have achieved '$100 million in ARR the fastest.' Later, some start pursuing '$1 billion in ARR the fastest.'

The problem is that this 'momentum' attracts more competitors and capital rather than creating a more robust moat. Competition makes already difficult business models even harder to sustain.

For example, in the code generation field, Cursor has already reached $1 billion in ARR, while companies like Lovable, Windsurf, and Devin have also exceeded $100 million in revenue. However, most of these companies heavily rely on Anthropic for computing resources and invest enormous sums in sales and marketing to acquire customers. The result is that their already fragile profit margins are further squeezed by the 'momentum of competition.'

The so-called 'momentum' may seem to make companies run faster, but it could actually be an accelerator toward a cliff.

/ 03 /

The 'Illusion' of AI Growth

As someone commented under Bryan's post 'Momentum Is the Only Moat':

'If you can go from $0 to $2 million in 10 days, you can also drop back to zero in 10 days.'

This highlights the biggest risk of momentum-driven companies—they can rise rapidly but also fall just as quickly. Many overhyped industries follow this pattern.

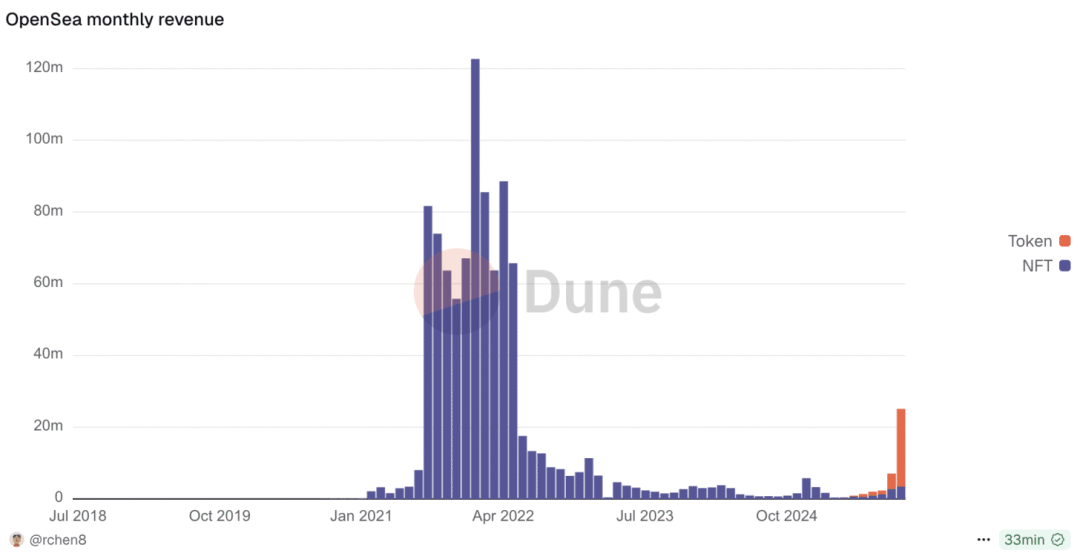

Take OpenSea, for example. During the peak of the 2021 crypto market, its monthly revenue reached $122 million, and the company's valuation soared to $13.3 billion. But once the hype faded and the market crashed, OpenSea has yet to recover to its former peak.

This doesn't mean OpenSea is a bad company. In fact, its annualized revenue is still $365 million, but it pales in comparison to its previous valuation. Investors who bought in at the peak have already suffered significant write-downs.

Worse still, this situation is all too common in today's AI industry. Many companies inflate their revenues to appear rapidly growing:

They count revenue from free trial periods as annual income; they annualize one-time project revenues; they even sell $2 worth of services for $1 just to make their growth curves look prettier.

This 'momentum'-driven growth is unsustainable. Investors aren't buying the company's true value but a short-term illusion.

Yoni Rechtman from Slow Ventures put it well: 'This is both a marathon and a sprint.'

The problem is that momentum-focused investors often only see the sprint. By the time the finish line appears, they're already out of breath.

/ 04 /

Momentum ≠ Innovation Speed

Musk said that moats aren't that important; what truly matters is the speed of innovation. But many misinterpret 'innovation speed' as 'market hype' or 'growth momentum.'

Alex Immerman, a partner at a16z, added a vivid analogy: 'Momentum isn't the moat; it's the boat.' Meaning, momentum can carry you to the island where you can build a moat, but it isn't the moat itself.

In the early stages, companies rely on momentum; only when you reach a certain scale can you truly build a moat. Even in the ChatGPT era, the essence of these moats remains unchanged—they still come from switching costs, network effects, economies of scale, branding, and proprietary data. The models are just more accessible now, product components are cheaper, and development is faster, but the defensive logic remains the same.

Musk's 'innovation speed' doesn't refer to how much you produce but your ability to drive innovation cycles. Many companies appear to grow rapidly with impressive revenue figures, but this is often achieved through burning cash or inefficient models and doesn't mean they truly possess an engine capable of consistently generating high-quality innovation.

True high-speed innovation comes from better products, stronger technological breakthroughs, and teams that can quickly eliminate inefficiencies.

Worse still, today's investors chasing 'momentum' are exacerbating the problem—they inflate short-term momentum while masking the lack of true innovation capabilities.

/ 05 /

Conclusion

When capital becomes abundant to a certain extent, it can actually obscure many problems. Every major company is scrambling to invest in those 'potentially next top 1% winners,' fearing they'll miss out. As a result, they're investing earlier and earlier—as soon as they see a hint of success, they pour money in.

The consequence is that many companies with unproven business models, unstable economic logic, and mediocre team execution can still secure massive funding. With more money and attention, they attract more talent, more capital, and more media exposure, making their inherently unhealthy models appear more like 'success paradigms.'

Worse still, this affects the next generation of entrepreneurs. Everyone starts copying these tactics: rapid fundraising, burning cash for expansion, and relying on short-term growth data to tell stories instead of refining truly sustainable products and business engines.

Momentum is important, but it's not a moat. What truly determines a company's fate is its ability to build a high-quality, long-term sustainable innovation engine. Treating 'chasing hype' as the core of growth will only make the entire ecosystem increasingly frivolous.

Ultimately, the top 1% of founders will remain—they'll create great companies regardless of capital's influence. The ones forgotten by time will be the middle 50% of companies: not the worst, but not the best, just those swept along by the tide and fading away.

By Lin Bai