Unraveling the Intricate Internal Competition in China's Auto Industry

![]() 06/11 2025

06/11 2025

![]() 675

675

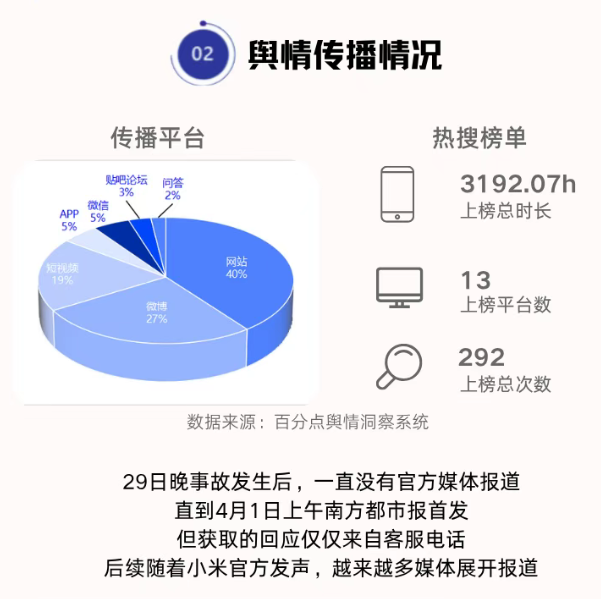

Last month, an accident involving Xiaomi Auto's intelligent driving system garnered nationwide attention, trending on Weibo for a week and significantly impacting Xiaomi Auto's reputation. While Xiaomi's profile soared, it left a lasting impression on the public that intelligent driving is unreliable and electric vehicles are unsafe.

In response, relevant departments promptly revised the terminology, now referring to intelligent driving as assisted driving, marking a significant step backward in China's autonomous driving development.

Lei Jun, known for his prowess in online marketing, kept a low profile following the incident, reducing his online statements. Xiaomi was subsequently plagued by a string of negative news, such as the ultra punch-hole controversy, which was initially about customized delivery and cost-effectiveness but was sensationalized as fraud. From being hailed as the most promising newcomer in China's auto industry to being besieged by negative headlines, the turnaround was swift.

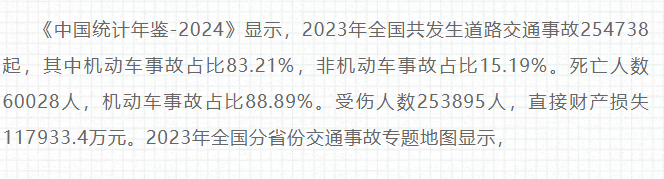

The performance of Xiaomi Auto did not fluctuate drastically, nor should the safety of intelligent driving and electric vehicles be judged by a single incident. In fact, China experiences approximately 5.23 million traffic accidents annually, with at least 15 fatalities daily. Considering the number of vehicles on the road, 80% of these accidents involve fuel vehicles.

Why don't these accidents make headlines? Is Xiaomi's incident the only one worthy of attention?

Repeating the same narrative ad nauseam fosters the illusion that it happens frequently, obfuscating the reality of big data statistics.

Behind this lies a focusing effect orchestrated by certain parties: what you see is only what they want you to see. When a lie is repeated three times, it often gains credence among the general public.

This underscores a critical issue: today's internal competition in the auto industry transcends price wars, evolving into cognitive warfare. Major media platforms serve as the primary battleground, where exaggerated, contradictory, and often unbelievable news proliferate, fostering an atmosphere of chaos within the industry.

Compared to technological iteration, gaining a competitive edge through cognitive and public opinion warfare has a lower threshold. What consequences has this internal competition borne? Have the initiating companies succeeded? What are they trying to conceal behind these headlines? These questions warrant in-depth investigation and assessment.

I. Low Industry Profits

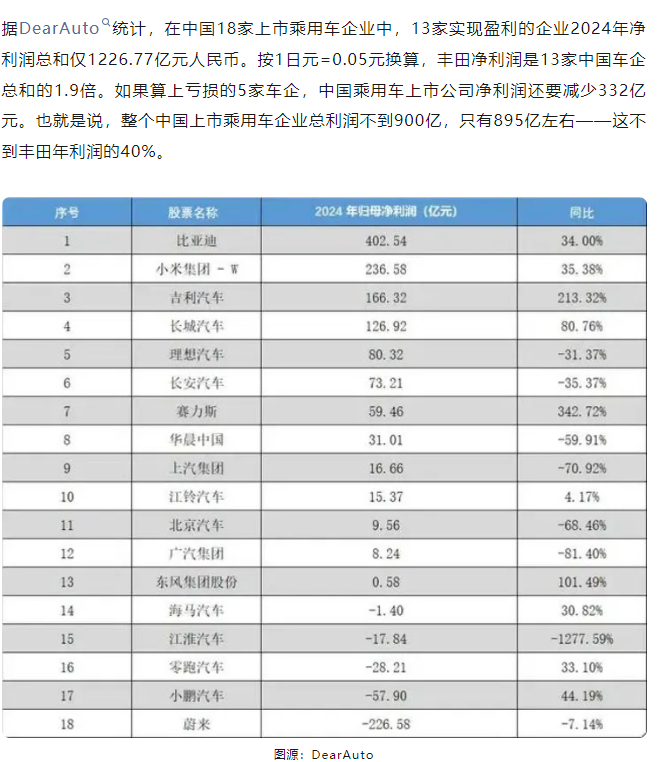

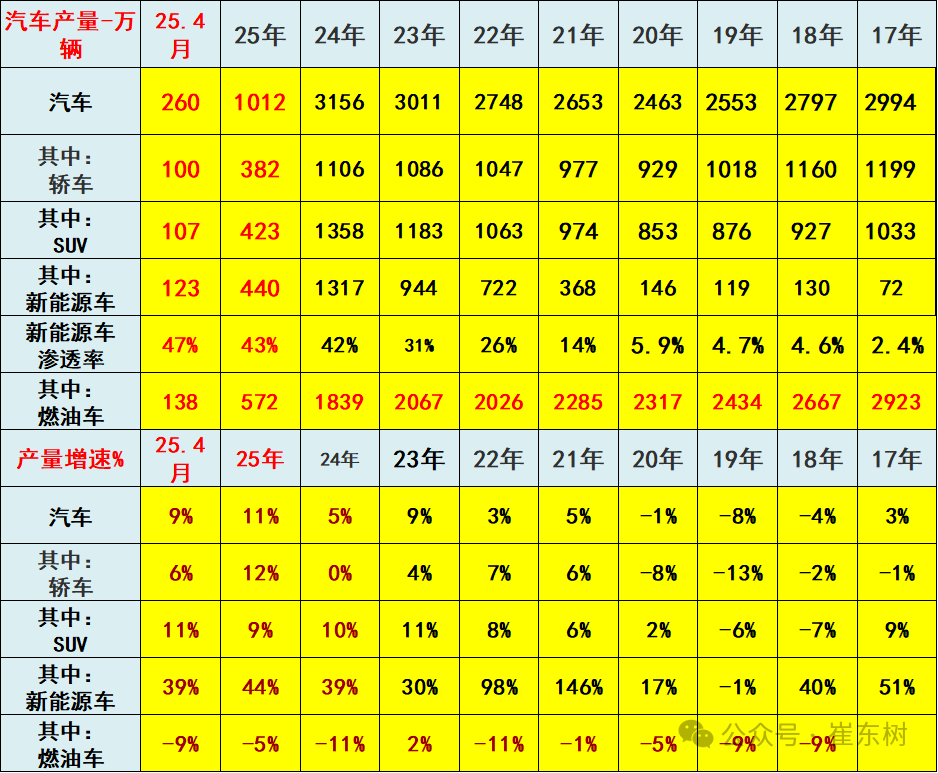

China's auto industry is growing rapidly, yet this scale expansion has not translated into profits. In 2024, Toyota's profit was 2.5 times that of all Chinese automakers combined. In 2017, China's auto industry's total profit exceeded 70 billion yuan, while Toyota's profit was 140 billion yuan, only twice as much. Despite domestic substitution rates exceeding 60%, profits have stagnated.

The underlying reason is the decline in market share for autonomous joint-venture OEMs like SAIC and GAC, releasing profits, while new electric vehicle players have gained market share but failed to achieve the anticipated profitability.

New electric vehicle forces exhibit weak profitability. For instance, GAC Group, a mid-tier joint venture player, peaked at 70 billion yuan in revenue and 3-4 billion yuan in profits during the fuel vehicle era in 2017.

Today, companies like NIO, XPeng, and Li Auto, with revenues nearing 60 billion yuan, remain unprofitable, with NIO deeply in the red. Despite eliminating cost-sharing with overseas automakers in supply chains, profits have not increased. Notably, Lixiang and Thalys, leading new forces, have witnessed declining profits despite sustained growth and increasing sales volumes, highlighting deeper issues.

These companies, once champions of market growth, have encountered significant setbacks. Lixiang faced hurdles with its mega models, while Thalys saw its intelligent driving accident amplified, both abruptly halting their performance growth.

II. How Cognitive Warfare Works

Lixiang and Thalys are fierce competitors, both focusing on large SUVs. Their setbacks reveal the role of speech in fueling the flames:

For example, the MEGA design was likened to a coffin. Thalys' intelligent driving and axle breaking accidents were compiled and repeatedly promoted. Conversely, FSD videos were scarce, leading to the impression that domestic intelligent driving lags behind FSD. However, with the entry of lower FSD versions into China this year, it became evident that Thalys and Lixiang's intelligent driving capabilities surpass FSD, revealing an underestimation of domestic intelligent driving capabilities and deliberate manipulation of past negative information.

This underscores an industry-wide chaos: slandering others is preferable to self-improvement. When an automaker thrives, it becomes a target for collective slander.

Through online troll armies and public opinion momentum, malicious posts about competitors are promoted, and exposure is bought on media platforms in large quantities. Simultaneously, "neutral individuals" are invited to exaggerate and distort incident reports, damaging competitors' competitiveness and reputation while boosting one's own products.

This is cognitive warfare—low-threshold yet highly effective. The cost is invariably lower than investing in research and development. Catching up technologically requires teams and material expenses amounting to several hundred million yuan, with no guaranteed performance improvement. In contrast, the effects of cognitive warfare are immediate; for instance, Xiaomi's order volume declined shortly after its incident.

Targets of cognitive warfare are obvious—companies with high market share and outstanding growth performance. The best students are always targeted by their peers. Cognitive warfare is typically initiated by those who stand to benefit, often through unplanned tacit cooperation, with even non-conflicting competitors joining in out of jealousy.

How was this discovered? Often, black pieces were exposed and promoted by different companies' public relations departments, leading to excessive exposure due to a lack of coordination in statistics and control.

This easily exposes the problem: even popular posts should not be repeatedly promoted so frequently. When hundreds of different people continuously post the same draft, and it appears on Xiaohongshu, Kuaishou, Douyin, Weibo, Bilibili, and Xueqiu without changing punctuation, it raises questions.

Moreover, cognitive warfare often waits for unfavorable news about the opponent to emerge before acting, amplifying negatives and adding fuel to the flames. Spraying on flat ground can easily backfire.

In the current industry, some mutual blackening relationships are easily identifiable, such as Xiaomi and Huawei, which have competed from mobile phones to automobiles. Other examples include overlapping model pricing among Lixiang, Huawei Thalys, and NIO; Xiaomi's seizure of Geely's track positioning and poaching of its team; and Tesla's overlapping models with Xiaomi. BYD, as the industry leader with full model coverage, is naturally a target for all.

Every company has been blackened to some extent, tied to its market position. If there's no sales volume, there's no attack.

This explains why after Xiaomi Auto emerged, there were no more news about Tesla's brake failures; instead, Xiaomi became the protagonist. In fact, one month after Xiaomi's accident (last week), Tesla was also involved in an accident where a car crashed into the rear of a large truck, severely injuring the owner, yet this news went unnoticed.

The reason is simple: Xiaomi has the fastest growth rate in the industry and is on the rise, while Tesla's sales in China are in free fall.

Of course, Xiaomi's cars have hardware deficiencies, with mismatched power and braking performance. This is not deliberate blackening; the accident rate supports this view. However, insurance premiums haven't risen significantly, and each accident hasn't caused major losses, proving it's not very serious. After all, it's a new model with flaws.

But this incident has been repeatedly amplified, implying messages like Xiaomi's intelligent driving is poor, Lei Jun exaggerated, Xiaomi cars are prone to collisions and fires, Xiaomi ultra punch-hole deceived users, and Xiaomi's insurance premiums increased significantly. This is a combination of punches with clear intentions.

III. Even Lower than Price Wars

So, is cognitive warfare effective? Judging by data, it's effective in the short term, as evidenced by Xiaomi's order decline following its incident.

But in the long run, it's futile. If you can do it, so can your competitors. The result is everyone having a black history online, with electric cars burning on startup and intelligent driving crashing on activation—definitely not the reality.

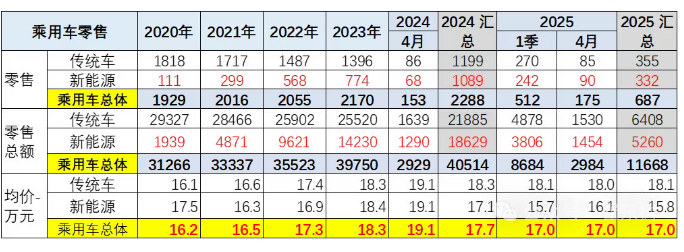

Today's price wars indeed involve price reductions, but the issue is that while prices fall, new energy vehicles compete for higher configurations.

This is puzzling. Why do upgraded configurations require lower prices for purchase? Observing that the average selling price of fuel vehicles has remained largely unchanged, while new energy vehicles' average selling price has declined, why are consumers so harsh on new energy vehicles?

Source: Cui Dongshu

Due to cognitive warfare, a few companies have gained minor benefits, but it's detrimental to the entire industry. Today, searching for any domestic auto brand on any domestic media platform yields mostly posts about malfunctions, accidents, and not being recommended, further deterring low-awareness and conservative users from adopting electric vehicles and intelligent driving.

In contrast, searching for any Chinese auto company brand on overseas media apps like YouTube, TikTok, and X yields cleaner comments.

Though China's electric vehicle penetration rate is high, it's still lower than expected. Battery and hybrid electric vehicles have surpassed traditional vehicles in economy, durability, performance, and experience, yet the switch hasn't occurred.

Endless cognitive warfare only slows overall growth, allowing low-priced, high-configuration fuel vehicles to capture conservative consumers' minds. This includes the industry's low profits and the suppression of emerging, high-performing forces—the repercussions of cognitive warfare.

Most importantly, cognitive warfare investment isn't reusable or cumulative. While expenses aren't high, the resulting path dependence inevitably dampens a company's research and development enthusiasm. Simultaneously, this advantage can't be transferred overseas.

Major global automotive giants thrive by offering discounts domestically and premium prices overseas. Going overseas is a top priority for Chinese automakers. However, companies relying on cognitive warfare as a competitive advantage have no overseas advantages and can't replicate their domestic success abroad.

First, over 200 countries lack a unified writing system and media like China. Posting in various languages is challenging, and distribution costs multiply.

Many countries' automotive industries still use traditional print media as the primary communication medium. Based on the internet and social media's recommendation algorithms, maliciously distributing and distorting right from wrong isn't easy.

Moreover, China's internet and media industries aren't strictly regulated by law, unlike overseas.

According to advertising laws, companies paying for self-promotion on online platforms must label it as "sponsored" or "advertisement".

Automakers paying for negative articles, rumors, and attack posts about competitors also benefit, and platforms like Douyin and Weibo receive money for it. However, this doesn't require "sponsored" or "advertisement" labeling, posing a serious issue.

Advertising is ubiquitous overseas, yet resorting to it to attack competitors often entails considerable legal risks.

Cognitive warfare is hardly a novel concept, with the United States' deployment against China serving as a quintessential example.

This strategy has persisted for decades, employing an array of classic tactics: leveraging the media extensively, orchestrating "neutral figures," exaggerating issues, fanning the flames of controversy, engaging in sarcasm, and covertly promoting oneself. It involves repeated promotion, twisting facts, generalizing from specific instances, and using individual cases to represent the whole. The paradox lies in its ever-changing narrative—today hyping the imminent collapse of something, tomorrow portraying it as a global threat.

Over these decades, many have indeed fallen prey to this narrative. Yet, ultimately, it has failed to yield tangible results due to China's unwavering foundations and continuous investment in basic science and technology to catch up. It is no surprise, then, that such sectors are now facing budget cuts.

In the current context, it is imprudent to pinpoint which companies are indulging in cognitive warfare. However, it is evident which companies are most likely to be tarnished, essentially determining who holds the upper hand in competition. If the legal landscape remains challenging, cognitive warfare within the domestic market is an inevitability.

In an environment characterized by low profits and diminished reputation, entities continue to deplete themselves.

Yet, there lies a silver lining: the overseas market is not only lucrative and vast but also less susceptible to cognitive warfare. It is a realm where real skills prevail. The more successful a company becomes domestically through cognitive warfare, the greater the challenge it faces in venturing overseas.

Take Chery, for instance, which maintains a modest presence and performs modestly in the domestic market without standing out. Consequently, there has been little attempt to tarnish Chery's image as it has yet to offend anyone.

Chery's total sales and profit performance have been steadily progressing, with its overseas market fortunes serving as the cornerstone. It has encountered no growth bottlenecks. In fact, automakers rarely face genuine growth constraints. Claims such as the inability to surpass monthly sales of 10,000 units or the annual sales cap of 600,000 units for new entrants are often man-made obstacles rather than objective laws.

This underscores that if a company possesses technological advantages, it should boldly monetize them overseas without fearing unorthodox tactics. When xenophobic and conservative users realize that overseas users recognize Chinese auto brands far more than the domestic market, their perceptions will crumble, and they will acknowledge their contradictions. The root of these contradictions lies in the information cocoons constructed by media narratives. Ultimately, they will set things right.

Conclusion

From this perspective, the internal competition within China's auto industry transcends mere price wars; it also encompasses the cognitive warfare underlying them. Price wars are commonplace across industries and are not problematic. Losing money now often paves the way for greater earnings later—a natural cycle. Industries like energy, mining, and maritime transportation engage in price wars daily.

No industry prohibits price reductions for promotional purposes. However, it is unusual for consumers to demand performance enhancements alongside price drops. The crux of the matter lies in cognitive warfare. This includes the misconception that China's auto price wars are improper and detrimental to suppliers. Much of this is biased, reflecting suppliers' emotional venting due to declining performance and subtle mockery among competitors.

In summary, the mutual attacks within the Chinese auto industry only tarnish its reputation. Consequently, increasing configurations while lowering prices becomes a strategy to counteract this decline. This situation is professionally termed a "negative-sum game" or simply a lose-lose scenario.

Returning to the initial case of Huawei AITO and Li Auto, the twin stars of new forces, they face mutually caused bottlenecks. In cognitive warfare, there are no winners.

Therefore, until China's internet media regulations and environment undergo revision, Chinese auto companies merit attention. However, the Chinese auto market should be avoided if possible, as 90% of auto news is "paid content." The key lies in going overseas. The more intense the cognitive warfare, the harder it becomes to venture overseas. Unfortunately, many companies still fail to recognize this and continue to mire themselves in the quagmire of cognitive warfare.