Preventing Food Delivery Services' Overseas Expansion from Becoming a Cycle of Inward Competition

![]() 08/25 2025

08/25 2025

![]() 571

571

Chinese enterprises caught in a cycle of inward competition should not use short-term tactics to mask their lack of long-term capabilities.

——Introduction

Recently, Didi Food Delivery has once again sued Meituan Food Delivery in Brazil.

The rationale behind this lawsuit is somewhat absurd: Didi Food Delivery, operating under the name 99Food in Brazil, filed a countersuit in a Sao Paulo court, claiming that Meituan Food Delivery's brand colors, graphics, and fonts are highly similar to its own, infringing on its trademark rights. Didi demanded that the court order Meituan to change its logo. Notably, 99Food is a result of Didi's acquisition of 99, a Brazilian ride-sharing giant, and the addition of "Food" to reflect its food delivery business. Didi's standard approach to entering overseas food delivery markets involves prioritizing cities where it already has a ride-sharing presence to maximize resource reuse.

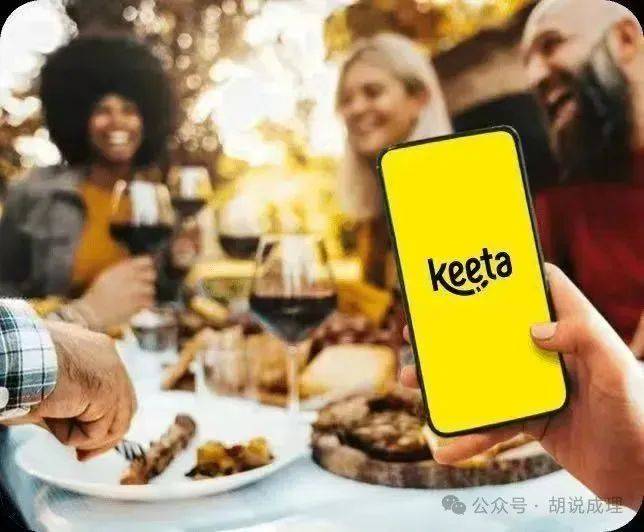

Meanwhile, Meituan's international business, named Keeta, continues to use its signature bright yellow color, which has been part of its branding for over a decade.

The absurdity of Didi's countersuit lies in the comical nature of the chosen legal angle: bright yellow has long been a prominent feature of Meituan's brand, while Didi's domestic brand color is orange – a fact that may not be widely known to foreigners.

Another ridiculous aspect of the lawsuit is 99Food's claim that, when viewed in a rearview mirror, the letters "ee" in Keeta's logo can appear as "99," implying a connection to 99Food.

In legal terms, there exists a type of lawsuit with no actual chance of winning but aimed solely at delaying the other party's actions or consuming their resources, commonly referred to as a strategic or dilatory lawsuit. Whether 99Food's lawsuit falls into this category is for legal professionals to decide.

However, it is a fact that 99Food's lawsuit is a counter-response to Keeta's lawsuit against 99Food, which has merit. On August 14, Keeta sued 99Food in a Brazilian court, accusing it of unfair competition practices.

Just before Keeta's entry into the Brazilian market, 99Food made aggressive moves: local sources report that 99Food has contacted over 100 restaurant chains, offering at least 900 million reais (over 1 billion yuan) in prepaid payments in exchange for exclusive agreements that prohibit merchants from cooperating with Keeta but require them to partner with local food delivery giant iFood.

Among these offers, the highest single prepaid payment is said to exceed 100 million yuan, typically reserved for chain restaurant giants with hundreds or thousands of stores.

However, these funds are not easily obtained. The exclusive agreements signed by 99Food with merchants include stringent breach clauses: a merchant that violates the agreement faces a penalty of at least 1.5 times the "initial incentive." In other words, Didi aims to block Meituan's cooperation with mainstream Brazilian restaurant brands on the eve of its entry into the Brazilian food delivery market, severely limiting its development potential.

In response, Keeta sued 99Food in court, stating in court documents that the "exclusive clauses" signed by 99Food with core merchants violate Brazil's Competition Act. Keeta seeks a court judgment to invalidate these clauses and prohibit their use in future contracts.

Brazil's Competition Act is somewhat akin to China's Anti-Monopoly Law, but the former appears to be more stringent. Under the Act, if a company's market share exceeds 20%, it may be deemed to "have a dominant market position," while domestic legal practice suggests a higher market share is required for such a definition.

In fact, to preemptively hinder Meituan's entry into the Brazilian market, 99Food has resorted to various unusual tactics, such as purchasing a large number of keyword ads for Keeta on Google search, redirecting them to 99Food or other results with partially similar characters. Meituan sued over this tactic, and on August 11, the court ordered 99Food to stop confusing "Keeta" keyword search results on Google and similar platforms within three days, with a fine of 20,000 reais per day for non-compliance.

Didi's fierce competition with Meituan before even gaining a foothold in the Brazilian market is largely due to the market's high value. The food delivery business thrives on scale, low profits, and strong operational attributes, creating greater value in larger, more economically dynamic economies.

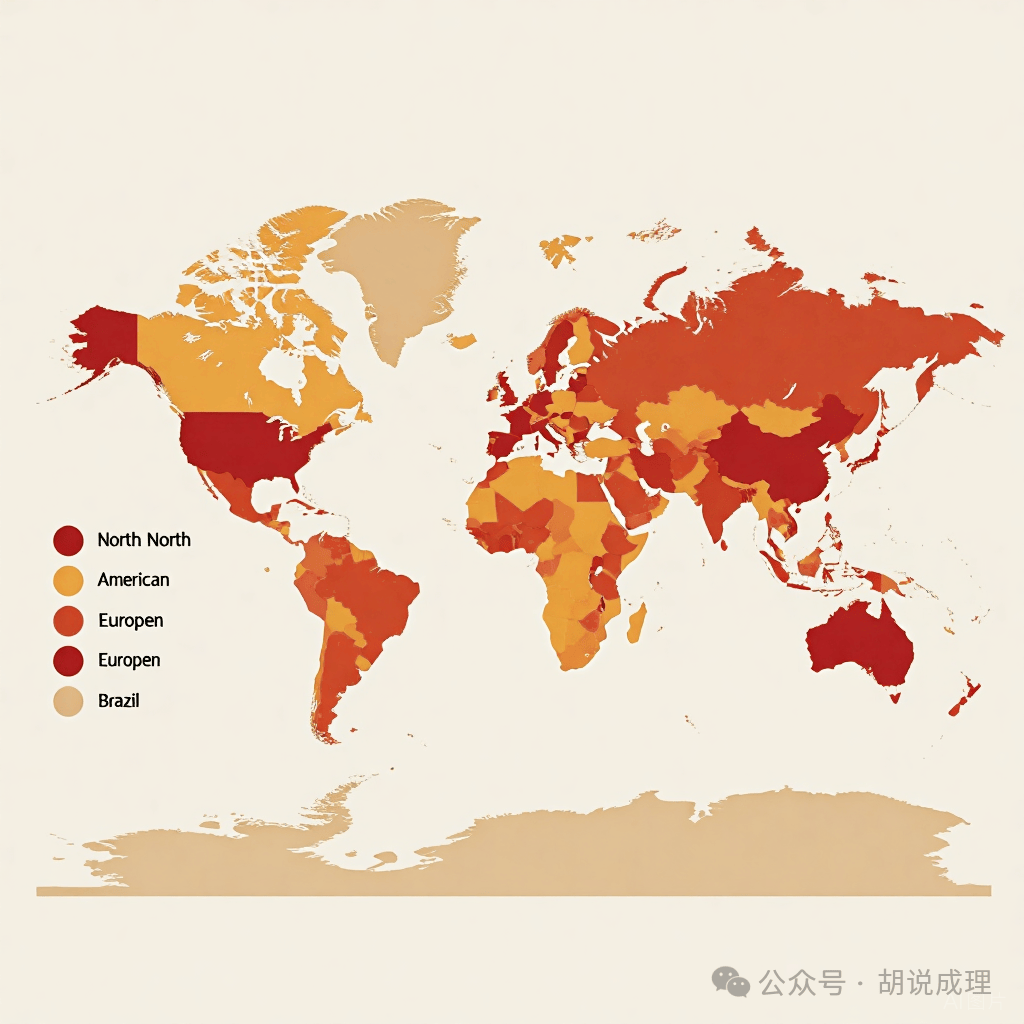

Among the global scaled food delivery markets, East Asia (with China as the mainstay, accounting for the largest share globally) is the largest, followed by North America and Europe. However, these markets are largely saturated. Relatively speaking, the next major overseas food delivery markets are the Middle East, where Meituan has gained a significant advantage, and Latin America, centered on Brazil.

More importantly, due to Brazil's demonstrative effect on other Latin American markets, capturing the Brazilian market is akin to securing a company's development prospects in the entire Latin American market, making it a crucial battleground in the global food delivery market.

Beyond the tit-for-tat struggles, several myths are worth considering in depth.

As a highly competitive business with limited cooperation, 99Food's approach is somewhat understandable. However, certain details raise questions.

The biggest mystery is why 99Food specifically targets Keeta rather than the local Brazilian food delivery giant iFood.

According to local Brazilian news, this "either-or" clause is primarily aimed at Keeta and does not restrict merchants' cooperation with iFood. With a market share of over 80% in Brazil, iFood's dominance is significant – Didi was defeated by iFood in 2023 and withdrew from the Brazilian market, with iFood using a "2 out of 1" strategy at the time.

Since then, Brazil's antitrust organization (CADE) formulated new regulations restricting iFood from signing exclusive agreements with merchants. However, this does not mean the "2 out of 1" strategy cannot be used in the Brazilian food delivery market.

It is said that 99Food once held up to 5% market share in Brazil but stagnated there.

Given that history has proven 99Food insufficient to gain a foothold in Brazil, why not change tactics?

In other words, since defeating iFood is unlikely, why not cooperate with Keeta, which has overall stronger strength (backed by Meituan) and is easier to communicate with (both being Chinese companies), to form a stronger, more complementary force? This would allow them to first target iFood and then divide the spoils after capturing more market share.

If the current approach continues, not only may the billion-level investment not be recovered for many years, but this approach has not effectively altered the Brazilian food delivery market landscape. Under predictable historical repetitions, what is the point?

Perhaps one can speculate that because Meituan's systematic capabilities and approach in the food delivery sector are proven to be more mature and efficient than Didi's, 99Food is wary of Keeta. However, such a high-profile approach seems to not only hinder Keeta but also greatly stimulate iFood.

Faced with the influx of Chinese competitors, iFood has already responded. On August 5, iFood announced in Brazil that it will invest 17 billion reais (about 22 billion yuan) by March 2026 to address pressure from international competitors like Keeta and 99Food, marking the company's largest investment plan in history.

In other words, 99Food's approach has yet to hit Keeta but has already awakened iFood. For this giant, such a high-profile provocation does not seem beneficial.

From another perspective, the Brazilian food delivery market's penetration rate is far inferior to China's, at just over 20%. Therefore, whether it's 99Food or Keeta, the market space they can compete for is not limited to the 80% controlled by iFood.

If the food delivery penetration rate in Brazil can approach China's 2025 level (with a penetration rate exceeding 50%) in the next five years, then as the overall pie expands, both new entrants and incumbent giants will have greater growth potential. This may explain why 99Food chose to exclude Keeta first.

We once believed that going abroad is the best path for China to advance globalization, expand external circulation, and hone the global competitiveness of Chinese enterprises.

A few years ago, I discussed the issue of going abroad with Yu Yongfu, the founder of UCWeb, who has extensive experience in the overseas expansion of Chinese Internet businesses. He shared an interesting viewpoint: when a company's true international competitiveness stems from superior technological innovation and strong brand value, it can project itself into the global market alone, like Apple and Google, whose overseas expansion is essentially "globalization." If these capabilities are lacking, one should proceed steadily, fully integrating localized operations and maintenance to cultivate and refine them, gradually achieving "internationalization" country by country and region by region, and finally establishing global influence. He bluntly stated that for the business capabilities of most Internet companies going abroad currently, it is more suitable to proceed steadily with the latter approach.

However, whether it's a one-step "globalization" or a steady "gradual internationalization," the essence should be a strategic choice to break through the growth ceiling and build global competitiveness.

But if enterprises view overseas markets solely as a "refuge" from domestic competition and inward spiraling rather than a "touchstone" to test their global competitiveness, they will not seek to establish solid differentiated competitiveness nor effectively project the advantages and capabilities established in China, the world's second-largest Internet market, internationally. Instead, they bring the inertial thinking of "price wars" and "traffic wars" unchanged to overseas markets, continuously staging "overseas versions" of homogeneous competition and even targeting Chinese enterprises going abroad together. This inward spiraling overseas not only benefits enterprises little but is also a concentrated outbreak of short-sighted corporate strategy, lack of capabilities, and disordered industry ecology, turning the global layout of Chinese enterprises into or even degrading it into "low-level expansion."

From this perspective, some inward spiraling behaviors overseas, while seemingly a "survival instinct," are actually the inevitable result of a lack of confidence in capabilities and the absence of differentiated competitiveness.

Chinese enterprises caught in a cycle of inward competition may seem to be "struggling to survive," but in reality, they are using short-term competition to mask their lack of long-term capabilities. If they cannot break free from the path of "subsidy dependence" and "traffic dependence" and establish a mindset of "long-termism" and "synergistic coexistence," even if they deploy their business globally, they will never truly ascend to the high end of the global value chain.