What Issues Can VLA Address in Autonomous Driving?

![]() 11/25 2025

11/25 2025

![]() 538

538

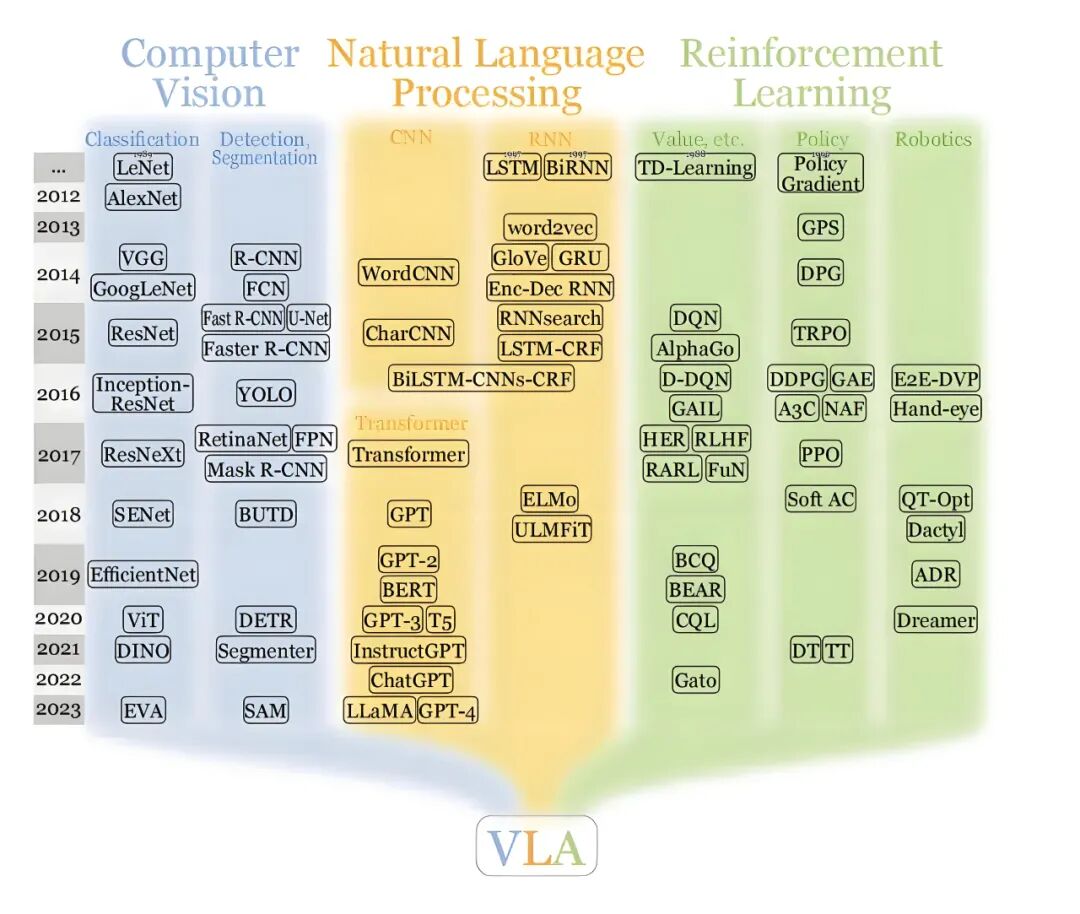

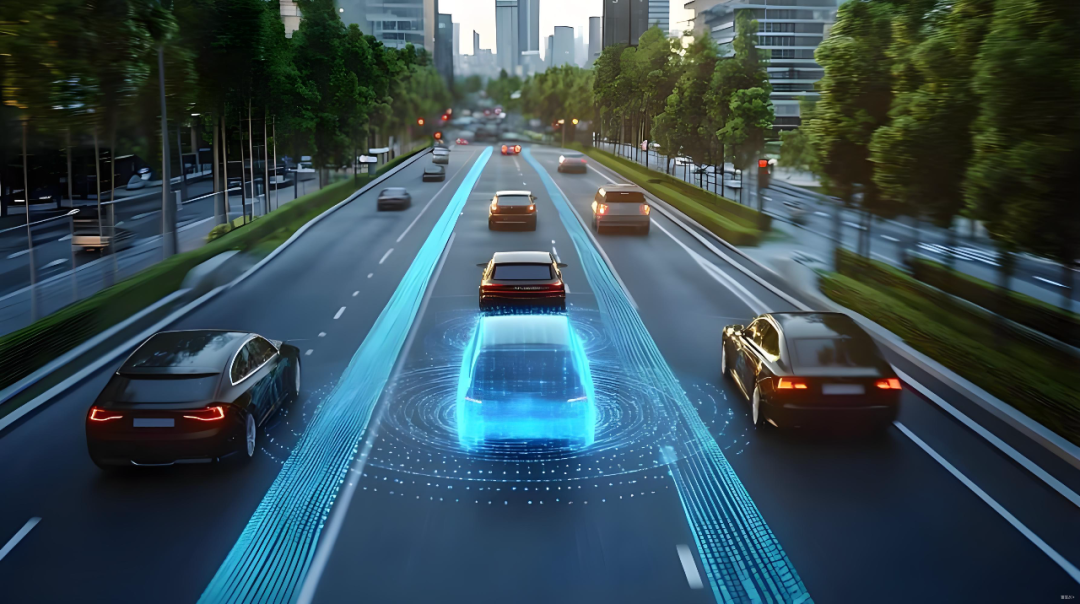

Many individuals involved in autonomous driving research are likely already well-versed in the concept of VLA. VLA, short for 'Visual-Language-Action' model, essentially integrates visual data, linguistic expressions, and action control into a cohesive model framework.

Unlike traditional autonomous driving systems that separate perception, prediction, planning, and control into distinct modules, VLA bridges the gap between 'what is perceived' and 'how to respond,' creating a model that directly maps visual inputs and language descriptions to specific actions or strategies.

Such models typically consist of a visual encoder (for processing images or point clouds), a language encoder (for interpreting text or instructions), and an action policy network responsible for outputting control parameters (such as trajectories or steering commands).

Image source: Internet

The integration of language into autonomous driving systems is not intended to enable vehicles to engage in conversation with humans but rather to utilize 'human-understandable semantics' to standardize and guide the model's learning process. By leveraging the conceptual abstraction and common-sense reasoning capabilities of large-scale language models, VLA can enhance the understanding and adaptability of autonomous driving systems when faced with complex, ambiguous, or rare scenarios. The breakthrough of VLA lies not in a singular enhancement of visual perception but in connecting 'environmental perception' and 'behavioral decision-making' in a manner that more closely resembles human cognition.

What specific issues can VLA address in autonomous driving?

Traditional perception modules are limited to outputting basic object category labels such as 'vehicle' and 'pedestrian,' lacking higher-level semantic information. Deep-level instructions, such as the reason a pedestrian is standing by the roadside, their intention to cross the road, or the meaning of a temporary sign reading 'Construction ahead, slow down and detour,' are difficult for traditional detection models to fully comprehend.

VLA can link visual evidence with language descriptions, such as associating a video frame with the statement 'The pedestrian is looking towards the road and may be preparing to cross,' thereby upgrading simple object detection to intent inference that includes scene understanding. This capability is particularly crucial in handling complex interaction scenarios like school zones, construction areas, or sudden traffic controls.

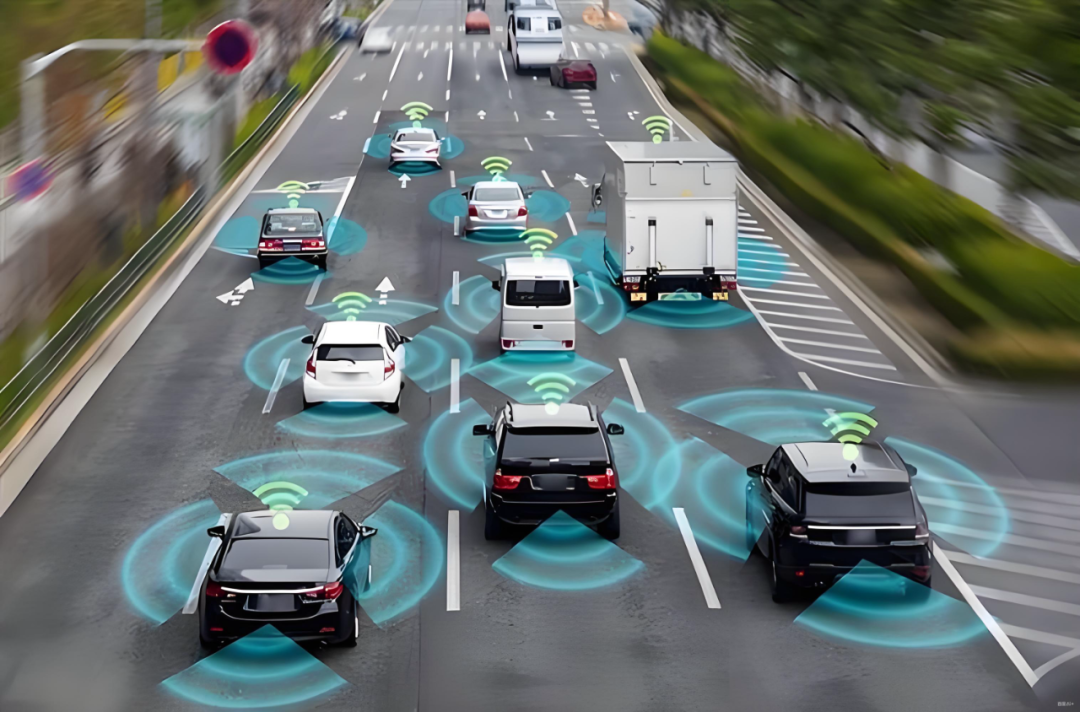

In real-world road environments, most situations are common and predictable. The true challenges for autonomous vehicles arise from rare, anomalous long-tail scenarios, such as unusually placed obstacles, non-standard temporary signs, or abnormally behaving road users.

Large-scale language models can transfer abstract concepts and common sense learned from vast amounts of text into the visual world through VLA's cross-modal training. For instance, a model may have never encountered a specific scenario, but if it has repeatedly come across descriptions like 'construction areas are often accompanied by cones, temporary road signs, and workers' in text, it can combine scattered visual cues into a high-confidence judgment of a 'construction scenario,' thereby adopting preemptive speed reduction or cautious driving strategies.

Autonomous driving systems need to interact with passengers, remote operators, or road maintenance personnel. Traditional systems have strict requirements for instruction formats and can only execute predefined action sets. VLA, on the other hand, can understand natural language instructions and directly translate them into vehicle actions or high-level strategies.

If a passenger says, 'I want to get off at the next exit, as close to the gas station as possible,' VLA can parse this vague and colloquial instruction, combining current location and map information to make corresponding lane selection and path planning. This is crucial for scenarios requiring human-machine collaborative decision-making or remote intervention.

Image source: Internet

Adapting traditional pure vision models to new scenarios requires a substantial amount of accurately labeled data. VLA, however, can utilize language as an 'additional supervisory signal' to achieve more efficient learning. Language descriptions provide abstract and transferable rules. By combining these rules with limited visual samples, the model can generalize and learn broader behavioral patterns. This holds significant practical value for rapidly deploying systems to new regions or achieving capability transfer through minimal labeling in simulated environments.

Black-box models are challenging to trace when decision-making errors occur, posing significant challenges for debugging and supervision. VLA, on the other hand, can provide a layer of semantic middleware that transforms visual cues into language descriptions and then drives behavior based on these descriptions. When a vehicle executes an action, the system can output natural language explanations like 'Slowed down and changed lanes due to detecting an unclosed construction area ahead with worker activity.' This greatly enhances the system's traceability and transparency, facilitating problem analysis and earning trust from regulators and users.

For autonomous vehicles, different sensors have their own strengths and weaknesses. Cameras may struggle under strong light or at night, while LiDAR may have poor perception of low-reflectivity objects in rain or snow. The large-scale cross-modal learning relied upon by VLA can achieve information complementarity at the semantic level. When visual perception is uncertain, language priors or historical descriptions (such as 'This section often has school buses stopping in the morning and evening') can provide valuable references, making decision-making strategies more robust. This function does not replace the physical redundancy of sensors but provides a valuable form of semantic redundancy.

End-to-end learning can directly map from pixels to control instructions, offering the advantage of strong generalization capabilities. However, it poses risks in terms of safety verification and controllability. VLA, on the other hand, represents a compromise path. It retains the generalization potential of end-to-end learning while introducing readability and intervenability through the language layer, making the system more user-friendly in terms of verifiability, parameter adjustment, and human supervision.

What key technologies and training methods are required to implement VLA?

Building a VLA system capable of operating on the road requires more than just stacking large models; it necessitates a comprehensive consideration of architecture, data, training, and deployment. VLA model architecture typically comprises three core components: a visual encoder, a language encoder (or a unified cross-modal encoder), and an action policy module.

The visual encoder extracts features from images or point clouds, while the language encoder converts text instructions into semantic vectors. These two are aligned in a shared semantic space. The action policy module is responsible for outputting specific control instructions (such as trajectories, steering angles) or high-level decisions (such as 'slow down,' 'change lanes').

Implementing a VLA model requires the collaboration of several technologies. The Transformer architecture serves as the core, acting as an 'information coordinator' specialized in handling the fusion of visual and linguistic information. Contrastive learning functions like a 'coach,' ensuring that the model understands that images and text descriptions refer to the same thing. Behavioral cloning and reinforcement learning are responsible for 'training' the policy network, enabling VLA to learn how to make correct driving actions.

To enable the VLA model to simultaneously master reliable visual semantics and linguistic common sense, the training set must include visual data, corresponding language descriptions, and matching action trajectories or decision labels. The annotation cost for such data is extremely high. In response, a hybrid data source strategy can be adopted, which takes precisely annotated real-world road data as the core, generates a large number of diverse scenarios using simulation technology, and supplements it with abundant online textual and graphical materials.

Image source: Internet

Another method to enhance data efficiency is to employ self-supervised or contrastive learning, such as having the model predict the next vehicle action or scene description on its own, thereby enabling the model to actively learn patterns from existing data and achieve cost-effective training results.

In terms of training strategy, VLA should adopt a phased approach. The first step is to conduct visual-language alignment pre-training, enabling the model to learn to establish connections between images and text. Next, behavioral supervision training should be carried out, such as through imitation learning or offline reinforcement learning, to have the model learn driving strategies. Finally, fine-tuning should be performed for specific driving tasks. In safety-critical applications, constraint optimization or independent safety layers must be introduced to ensure that the model's output behavior always remains within safe boundaries, allowing the system to override even aggressive suggestions from the model.

There is an inherent contradiction between the massive computational power required by large models and the limited resources of onboard hardware. Models must be streamlined (compressed and quantized), and a hierarchical deployment scheme must be adopted. To address this issue, the most computationally intensive tasks of language understanding and complex reasoning can be completed in the cloud or on edge servers, while only a lightweight inference engine, along with a safety monitoring module to ensure real-time safety, runs on the vehicle. The system also needs to possess dynamic scheduling capabilities, leveraging the 'cloud brain' when the network is good and seamlessly switching to a local traditional control stack when disconnected to ensure basic functional safety.

Image source: Internet

While enhancing interpretability, VLA models may also apply learned linguistic common sense inappropriately to unsuitable visual scenarios or misjudge ambiguous or even malicious instructions. To proactively expose and mitigate such risks, highly targeted scenarios must be designed during the testing phase, such as specifically examining the model's performance when faced with unconventional instructions and whether its semantic understanding remains consistent across different regional and cultural backgrounds.

In this process, high-precision simulation platforms play a crucial role. They can efficiently and safely simulate a large number of rare long-tail scenarios in reality, systematically verifying the reliability of model behavior and precisely locating its failure boundaries.

The requirements for VLA models in vehicle applications go beyond merely performing well; they must have clear response plans in extreme or failure scenarios. Therefore, VLA systems cannot operate independently but must work in conjunction with traditional and rigorously certified safety monitoring modules (such as automatic emergency braking, hardware speed limiters, etc.). The language module can be responsible for providing decision explanations and behavioral suggestions, but the ultimate control of the vehicle, especially safety-related execution instructions, must always be under the strict supervision of the functional safety system.

Final Thoughts

VLA embeds a 'semantic intelligence layer' into autonomous driving systems, endowing vehicles with the critical ability to understand complex scenarios and human intentions by connecting vision and language. However, it cannot replace traditional architectures but should work in conjunction with them. As an innovative cognitive brain, VLA can handle uncertainty and long-tail problems, while rigorously certified traditional control systems can serve as a safety foundation, ensuring flawless final execution. This hybrid architecture, where intelligence and safety coexist, represents a pragmatic path for the steady advancement of autonomous driving.

-- END --