Swallowing the Last Independent Player, Meituan Aims for More Than Just Fresh Groceries

![]() 02/10 2026

02/10 2026

![]() 460

460

Swallowing Dingdong Maicai for $5 Billion: Meituan Still Comes Out Ahead. The Money Buys Assets on the Surface, but in Reality, It Buys Efficiency, Defense, and Strategic Initiative.

Author | Zhang Xiansen

Editor | Yang Ming

The last independent player in fresh grocery e-commerce is gone.

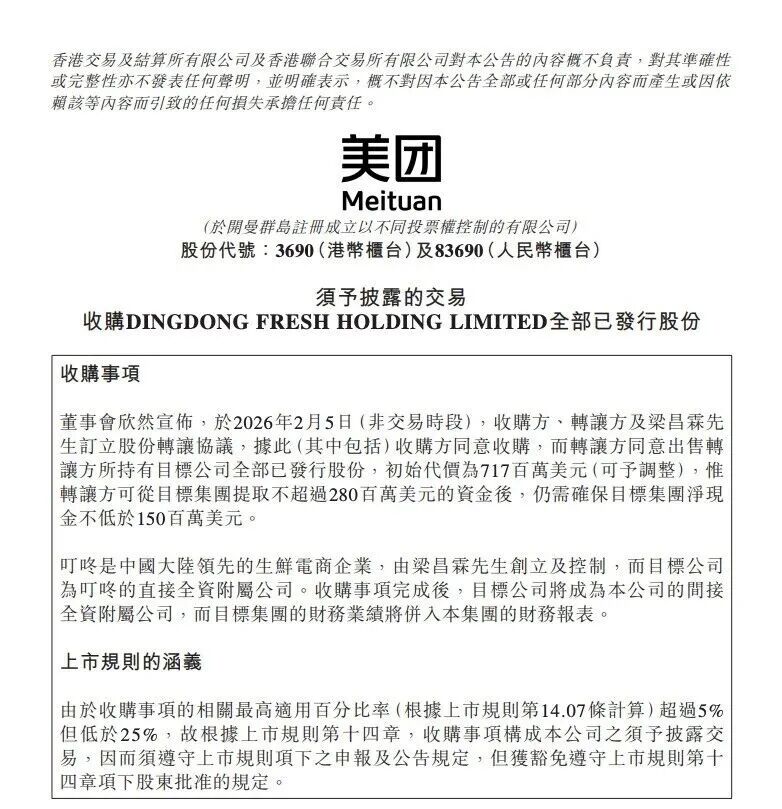

On February 5, Meituan announced in a listed company notice that it would acquire all shares of Dingdong Maicai and its China operations for an initial price of $717 million (approximately RMB 5 billion). Following the acquisition, Dingdong Maicai will become an indirectly wholly-owned subsidiary of Meituan, with its financial results consolidated into Meituan's reports.

While the transaction amount may not rank among the largest in internet M&A history, it carries a poignant significance for Dingdong, which has been locked in fierce competition for nearly a decade. Once hailed alongside MissFresh as the “Dual Champions of Front-End Warehouses,” Dingdong Maicai, after nine years of independent operations, has finally been absorbed into a tech giant's ecosystem.

Market rumors had long suggested JD.com as the most likely buyer for Dingdong, but this turned out to be a smokescreen for Meituan's swift move. Why would Meituan, bleeding in the food delivery wars, acquire Dingdong, a company with a highly overlapping business? Was this a defensive or offensive maneuver, a bargain hunt or a burden? As fresh grocery e-commerce shifts from “burning money for scale” to “efficiency determines survival,” can Meituan digest Dingdong and achieve a “1+1>2” outcome?

01 The Mid-Game Interception: Why Meituan Made Its Sudden Move

That Dingdong Maicai was for sale was no secret; the unresolved question was who the buyer would be.

Since late 2025, Dingdong Maicai founder Liang Changlin has stated internally that the domestic fresh grocery front-end warehouse sector is no longer viable for startups alone, and selling the company has been placed on the agenda. Meanwhile, market rumors repeatedly surfaced that JD.com was in talks with Dingdong, intending to fill gaps in its instant retail infrastructure through acquisition.

Presumably, JD.com was hesitating, but pragmatic maneuvers were underway behind the scenes. On February 5, Meituan's announcement that it would acquire Dingdong for $717 million sent shockwaves through the retail market. Why Meituan? And why so suddenly?

Sources indicate that last year's escalating food delivery wars altered Meituan's investment logic. JD.com's prolonged due diligence without finalizing the deal created an opening for Meituan, which seized the initiative.

From Meituan's perspective, this was first and foremost a defensive acquisition. As instant retail competition enters a phase where “infrastructure determines victory,” front-end warehouse networks are no longer mere cost centers but strategic assets. If JD.com acquired Dingdong, it would gain an instant delivery network covering eastern China and penetrating first- and second-tier cities, becoming a beachhead for attacking Meituan's core territory. Meituan was unwilling to cede such infrastructure or face higher defensive costs in the future.

Secondly, this was a crucial step for Meituan to address its supply chain weaknesses. While Meituan excels in delivery logistics, it lacks depth in the supply chain, particularly for fresh groceries—a high-frequency, high-perishability, and high-experience-requirement category. Its Xiangxiang Supermarket, also a front-end warehouse model, still lags behind Dingdong, which has nearly nine years of deep experience, in product variety, direct sourcing capabilities, and quality control systems.

More profoundly, Meituan is advancing a comprehensive upgrade of its instant retail strategy. In 2025, Wang Xing explicitly made instant retail a core strategy and proposed a grand vision of covering “16 major consumption scenarios.” Fresh groceries, as the highest-frequency entry point, are key to unlocking the “everything-to-home” scenario. Acquiring Dingdong is not just about buying warehouses and users but acquiring a mature fresh grocery operations system, injecting substantive content into its ambition to “deliver anything.”

Meituan's move reflects its forward-looking judgment on industry trends. The window for independent survival in fresh grocery e-commerce is closing. Whether it's MissFresh's collapse or Dingdong's choice to “land safely” after achieving profitability, both indicate that small and medium-sized platforms struggle to survive amid giant competition.

Essentially, this was a critical strategic move by Meituan before the sector upgrades. Allowing JD.com to acquire Dingdong would leave Meituan vulnerable to attacks from both Hema (Alibaba) on the left and JD.com on the right in eastern China, with defensive costs rising exponentially. The best defense in business is to acquire the assets your rival wants before they do.

02 Meituan's Calculations and Dingdong's Dilemma

While the deal seems sudden, for Dingdong Maicai, which has been pursuing self-rescue through an “efficiency-first” strategy, it is both a reluctant choice and an inevitable outcome of market consolidation.

Founded in May 2017, Dingdong Maicai entered the fresh grocery sector with a front-end warehouse model, offering “direct sourcing from origins + delivery within 30 minutes” and rapidly rose to prominence. The front-end warehouse model involves setting up small warehouses within a 3-kilometer radius of communities to enable stockpiling, sorting, and rapid delivery. Its core advantage is speed, but the cost is exorbitant—warehousing, cold chain, sorting, and rider fulfillment costs often exceed RMB 10 per order, a heavy burden.

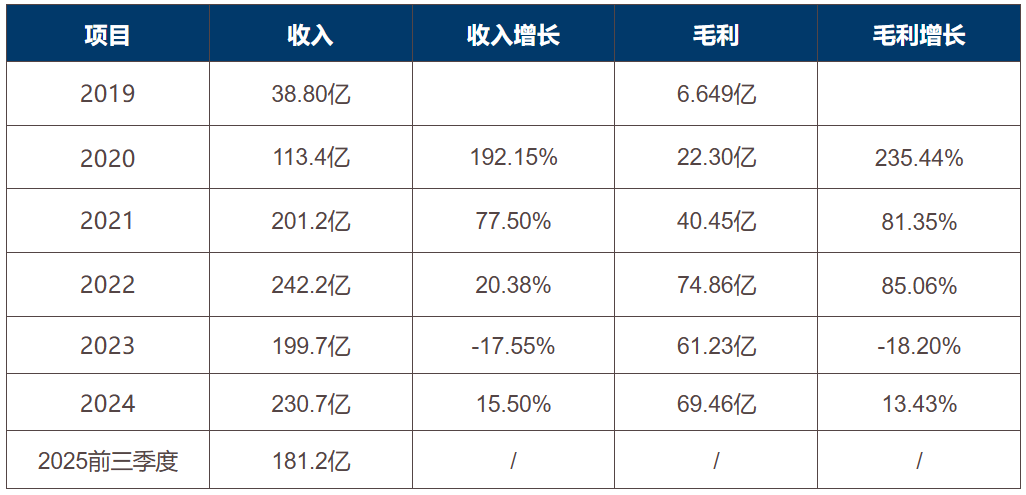

Nevertheless, Dingdong Maicai persevered with its front-end warehouse model, surviving industry shakeouts and emerging as one of the few survivors of the capital winter, following Yonghui Life's exit and MissFresh's collapse. Financially, Dingdong has been profitable for multiple consecutive quarters, with Q3 2025 revenue reaching RMB 6.66 billion and net profit RMB 80 million.

Dingdong Maicai's financial report

Why would a profitable company rush to sell? And is it worth it for Meituan to acquire a platform so similar to its own?

To understand this deal, one must see the concerns beneath Dingdong's halo (halo). Despite profitability, its growth has stalled. Q3 2025 revenue growth slowed to just 1.98% YoY, a significant deceleration from the previous two quarters. This reflects near-saturation in its core eastern China market, trapping it in a regional cage: unable to expand nationwide or sustain its position locally. Shifting from national expansion to regional deepening, Dingdong lost its growth narrative, leading to persistently low valuations in the capital markets, hovering around $500–700 million.

More critically, Dingdong's so-called “regional moat” is being eroded by giants. Meituan's Xiangxiang Supermarket continues to intensify its presence in eastern China, Hema restarts front-end warehouse expansion, and Pinduoduo attacks with low prices. Competitors are eroding Dingdong's user base with richer product offerings and faster price adjustments. Dingdong attempts to counter with “quality differentiation,” targeting high-end users. But high quality means high costs, and fresh grocery users are highly price-sensitive, making this path narrow.

At internal meetings, Liang Changlin repeatedly asked his executive team: “What if Meituan follows suit?”

This scenario reflects Dingdong's anxiety as an independent platform: in the instant retail battleground, where models are transparent and capital deeply involved, local innovations are quickly replicated by giants, and startups' hard-earned differentiation advantages are often erased within a few subsidy cycles. Liang's question was not about competitive strategy but the survival proposition of independent fresh grocery e-commerce amid giant ecosystems.

In contrast, Wang Xing is not after Dingdong's profit margins. With a net profit margin below 2%, the figure is negligible to a giant. For $717 million, Meituan is not just buying Dingdong's nationwide network of over 1,000 front-end warehouses (about half in eastern China) but a complete regional operations system and a validated high-value user ecosystem.

On one hand, Dingdong has built in eastern China not just a dense warehousing network but a refined operations system deeply embedded in the regional consumption ecosystem over nine years. It integrates direct sourcing supply chain depth, mature quality control standards, and precise understanding of eastern Chinese user preferences—core weaknesses in Meituan's self-operated business that have long resisted tackle key problems (assault).

On the other hand, the acquisition brings not just 7 million monthly active users but a validated, high-stickiness, high-repurchase fresh grocery consumption ecosystem. The behavioral data, consumption habits, fulfillment efficiency models, and membership operations methodologies supporting these users form a user operating system with immediate commercial value, which Meituan can directly adopt.

If Meituan were to build an equally dense network independently, the capital costs aside, it would take at least 2–3 years. More critically, fresh grocery users have extremely high migration costs, and regional mindshare, once formed, is incredibly difficult to disrupt. Dingdong's user recognition in eastern China is trust that Meituan cannot buy with even massive subsidies.

From this perspective, Meituan still comes out ahead. The money buys assets on the surface but in reality buys efficiency, defense, and strategic initiative.

For Dingdong's management, this is not a bad outcome. Cashing out early and exiting is the inevitable fate of independent fresh grocery e-commerce, as demonstrated by MissFresh's earlier collapse. For Dingdong's investors and management, factoring in the $280 million in cash they can withdraw, exiting gracefully at around $1 billion represents a sober cash-out at the capital level.

03 Integration Challenges: Can Meituan Digest Dingdong?

Acquisition is just the beginning; integration is the real battleground.

Meituan's first challenge is managing the internal competition between its “two sons.” Xiangxiang Supermarket and Dingdong Maicai share similar models, overlapping user bases, and regional clashes, yet differ in systems, teams, and corporate cultures. A simple merger would cause internal friction; maintaining independence raises questions about synergy.

A deeper challenge is avoiding Dingdong becoming a second “Dada”—a business gradually hollowed out, its team marginalized, and reduced to a mere logistics network.

To prevent this, Meituan is likely to adopt a “dual-brand independent operations + gradual backend integration” strategy. The Dingdong Maicai app will probably remain, preserving its brand mindshare and user habits in eastern China; Xiangxiang Supermarket will continue covering broader categories and scenarios. In the backend, their supply chains, warehousing systems, and delivery networks will gradually integrate.

The most promising area for integration is the delivery system. Dingdong's fulfillment costs have remained high (around 21.5% of revenue), while Meituan possesses the industry's most powerful rider network and dispatch system. If Dingdong's orders tap into Meituan's logistics pool, per-order delivery costs could drop significantly, while improving rider order density and utilization—achieving mutual cost reductions and efficiency gains.

At the supply chain level, Meituan can combine Dingdong's fresh produce direct sourcing capabilities with Xiangxiang's standardized product supply chain to create a richer product matrix. Leveraging Meituan's larger order volume, it can also negotiate better procurement prices upstream, further strengthening cost advantages.

However, the integration process is fraught with risks.

First is organizational and cultural conflict: How will the two companies' teams merge? Can Dingdong's employees adapt to Meituan's pace and culture? Second is system integration complexity: Aligning order, warehousing, delivery, and membership systems requires time and technical investment, during which user experience may suffer.

Additionally, Meituan must balance Dingdong's relationship with Xiangxiang Supermarket, Flash Warehouses, and other business lines. Flash Warehouses, as a platform model, prioritize rapid expansion and light asset operations; Xiangxiang and Dingdong represent self-operated, heavy models. How these three can coexist without internal friction tests Meituan's strategic resolve and operational wisdom.

04 Conclusion: A Deeper War Begins

Meituan's acquisition of Dingdong Maicai marks China's fresh grocery e-commerce sector's entry into the “tech giant ecosystem era.” Independent platforms are gradually exiting the stage, and future competition will be a comprehensive battle among Meituan, Alibaba, JD.com, and others in supply chain, efficiency, and ecological synergy.

For Meituan, this deal is a critical move to solidify its leadership in instant retail. Through Dingdong, it addresses fresh grocery supply chain gaps, strengthens its eastern China presence, and strategically prevents competitors from growing stronger.

However, acquisition is just the means; the real test lies in successful integration, achieving synergy, and whether Meituan can maintain organizational vitality and financial health amid ongoing attrition wars.

For the industry, this acquisition signals a complete shift in competitive logic: the era of burn-money subsidies is fading, and efficiency, supply chain, and user experience will become the core. The second half of instant retail will be a protracted battle focused on refined operations. Meituan's move is both a stimulant and a starting gun.

A harsher, deeper war has begun.